I have been thinking a lot recently about the benefits of not pretending to know stuff, of putting oneself consciously at a place of not knowing in order to be more open to explore what is possible. This is an attempt to write this down. The thinking is not finished and needs much more refinement, so please bear with me – and share your own reflections this might evoke in the comments.

The inspiration for this has come from different directions. Firstly, Dave Snowden introduced a new way of looking at the central domain of Cynefin that used to be called ‘disorder’ earlier this year. It is now called ‘confused/aporetic’, with aporetic being the mentioned state of putting oneself consciously at a point of not knowing. The second influence was a piece on education Nitzan Hermon asked me to comment on, which has unfortunately not been published yet – but he allowed me to use some quotes from it in this post. Finally, I listened to a very inspiring episode of the On The Edge podcast, in which Roland Harwood interviews Steve Xoh, an artist who works a lot with using not knowing (or rather aporia) in a playful way – and a subsequent very inspiring chat with Steve.

Education: a journey from not knowing to having to know

As young children, our minds are wide open to learning. Many, if not most of the things we encounter each day are new. Only when we grow older, we start to think we should know stuff. This is strongly encouraged by our society, culture, and the way we educate our children. At school, we are rewarded for knowing things during exams, not for asking questions or saying ‘I don’t know’.

The educational pursuit is well-intentioned, but its foundation is a reliance on a monolithic view of the world. It is deterministic in knowledge and allows for little true diversity. It puts blinders on the existence of individuated experience and the range of possible futures.

Nitzan Hermon

Yet, we cannot understand the world and all that is happening by all of us buying into a single, monolithic view of how things work. Large parts of how the world works are fundamentally unknowable. While research has uncovered incredible amounts of knowledge, it remains incapable of predicting natural phenomena like the weather for a significant amount of time. Let alone predicting human behaviour. And that is not due to a lack of trying, but because of the nature of many natural processes, including human behaviour and relationship. It is, in principle, impossible to predict those precisely over longer periods of time.

In this context, knowing becomes a disadvantage. Knowing comes with a price, it shuts down alternatives.

Knowing comes with a price. It asks to freeze reality, write scripts, roles, and goals for ourselves, and the spaces we meet, learn, and work. It asks for solutions to be designed, put in place, and stay in their original design, incrementally adapted for externalities.

Nitzan Hermon

This is compounded by the times we live in. The times are changing. Knowing something was of much higher value when we lived in a world in which a larger share of value creation was dominated by repeatable tasks, by producing something. Nowadays, all tasks that are repeatable, all knowledge that can be written down, reproduced, re-used, will be taken over by machines sooner or later. What will not be taken over are the tasks that require us to navigate the unknowable, uncertain environment of human relations and complex ecologies of mind.

… we forget that linear, efficient thinking operates within the world of limited material. If I were an artisan, I had limited material; using that material wisely would have a felt effect on my studio. But the modern knowledge worker lives in a world of abundance. And in abundance, it is context – masked as a question, inquiry, ways of thinking – which is scarce.

Nitzan Hermon

The map is not the territory …

Knowledge is always abstraction, taken away from a specific context. All the knowledge we accumulate builds up our mental models of how the world works. Yet they are just models, maps that help us navigate reality without spending too much cognitive energy.

If we think about it, our lives essentially start at a place of not knowing – we don’t have a lot of knowledge encoded in our genes. When we are born, or even before, our senses start exploring. Sounds, light and shapes, touch, smell, things come into focus. Sensory experiences first create and later evoke memories. Once this tapestry of experiences is shaped, sensory inputs don’t fall on a blank sheet anymore and are always interpreted in the light of things experienced earlier. This is an important thing to be aware of. Some neuroscientists even think that our brain only processes sensory inputs when they are different from what the brain predicted it would receive while ignoring the rest.

Hence, knowing takes us away from the territory and puts us on a map that we have created in our minds. That is not a bad thing per se, as our big brains need to save energy. It becomes a bad thing if we confuse the map with the territory – if we think what we know actually represent reality.

Understanding the way our brains work also imply, however, that we are only able to put ourselves at a place of not knowing to a limited extend. Hence, a diversity of view points that are loosely held are always better than a homogenous, strongly held and enforced world view. More to ponder about here …

A beginner’s mind and the Art of not Knowing

To function well in this world, we need to become better at not knowing, at being at a loss. I think that is what is often referred to as a beginner’s mind. This allows us to start any exploration from the territory, rather than the map.

Not knowing is difficult. It is uncomfortable. Not knowing often makes us talk too much, somehow trying to paint over the fact that we don’t know. Pretend we do. Yet if we allow for the silence and for the discomfort it creates, something creative can emerge. In the podcast episode referenced above, Steve Xoh talks about a time when he ran dialogue exercises in a corporate setting and recounts that particularly the moments of silence proved to be very powerful:

… it was always in those moments of sitting in a discomfort for a little bit longer than normal that something new emerges. And particularly sitting in a discomfort of disagreement and difference and confusion, and all of those things, something different always emerged.

Steve Xoh

Creativity exists in unknowing. How can we be playful with not knowing? How can this lead to creativity, new ideas, innovation?

As humans, we have a natural tendency to favour the concrete, the structured, the tangible, the predictable. We prefer the certainty of an imaginary structure to the ambiguity of reality. We are creating scripts that we can repeat, based on past experiences. Yet in reality, there is no script that we can repeat and even if we did have a script, we have never lived in this very moment before. Trusting blindly in such a script is problematic, to say the least.

Unknowing helps us to let go of scripts and to be creative, to improvise our way through the ever-new realities we are facing.

That is not to say that structures are completely useless. We need a certain amount of certainty and predictability in order not to overwhelm our brains. That limited cognitive capacity is why we create such structures, both internally in the way we make sense of the world, as well as in society, in the way we interact and relate to each other. Our big brains need to conserve energy.

It is a fine balance to know when to stick to the structure in order to reduce cognitive load and when to let go of it and improvise because the structure is inadequately adapted to the actual situation we face. That puts us in a constant tension.

… the moment we start to believe something as concrete we lose the ability to wonder, to imagine. And that’s the tension that I talk about, between creativity and the human condition. Creativity is our imaginations pulling towards the infinite and the amorphous and the weird and the wonderful; the human condition is our logic, our reason pulling towards the concrete and tangible and that tangible is always so much more appetising.

Steve Xoh

The concrete and tangible has taken over in our current world. Best practices are abundant, improvisation is frowned upon. Standard operating procedures and scripted algorithms are lauded, human intuition looked down at, seen as biased.

I think this is a big part of the reason why we are stuck; why we are facing multiple social, environmental and spiritual crises; why we do not seem to be able to respond to a changing climate, spiralling inequality and radicalisation.

We have the re-learn how we can move ourselves towards a place of not knowing. Not knowing allows us to wonder more, allows us to be curious. Not knowing as first step to shake the stage, to loosen some constraints and make new and different things possible. It puts us back on the territory of reality, away from the maps we have built up and we constantly confuse with reality. Not knowing as action; opening up more possibilities to act. Yet, how do we act when we don’t know what to do? This is a question I want to explore further.

Cynefin and Aporia: when not knowing is useful

I don’t want to say in any way that knowing stuff is not useful. On the contrary, it is immensely important to know, for example, how to grow food, how to build houses, how to keep them warm, how to cure our diseases and so on. Yet the knowledge and expertise we have internalised shapes the way we approach a problem. If we are an expert in economics, we tend to look at everything as an economic problem. If we are ecologists, the nature and ecological systems become the point of reference. Those are the maps we use to orient ourselves on the complex territory of reality. It might be stating the obvious, but these maps are generally not a very accurate representation of the problems we are facing. Particularly because reality does not happen in a single context. In the real world, problems are always an entanglement of multiple contexts. We cannot fix poverty by only looking at the economy, we also need to take into account culture, education, politics, technology and so on. We cannot fix climate change by only looking at shifting to electric cars or avoiding single-use plastic, we also need to look at broader consumption patters, mobility patterns, resource use, justice, etc. This links back to the idea of Warm Data I wrote about earlier.

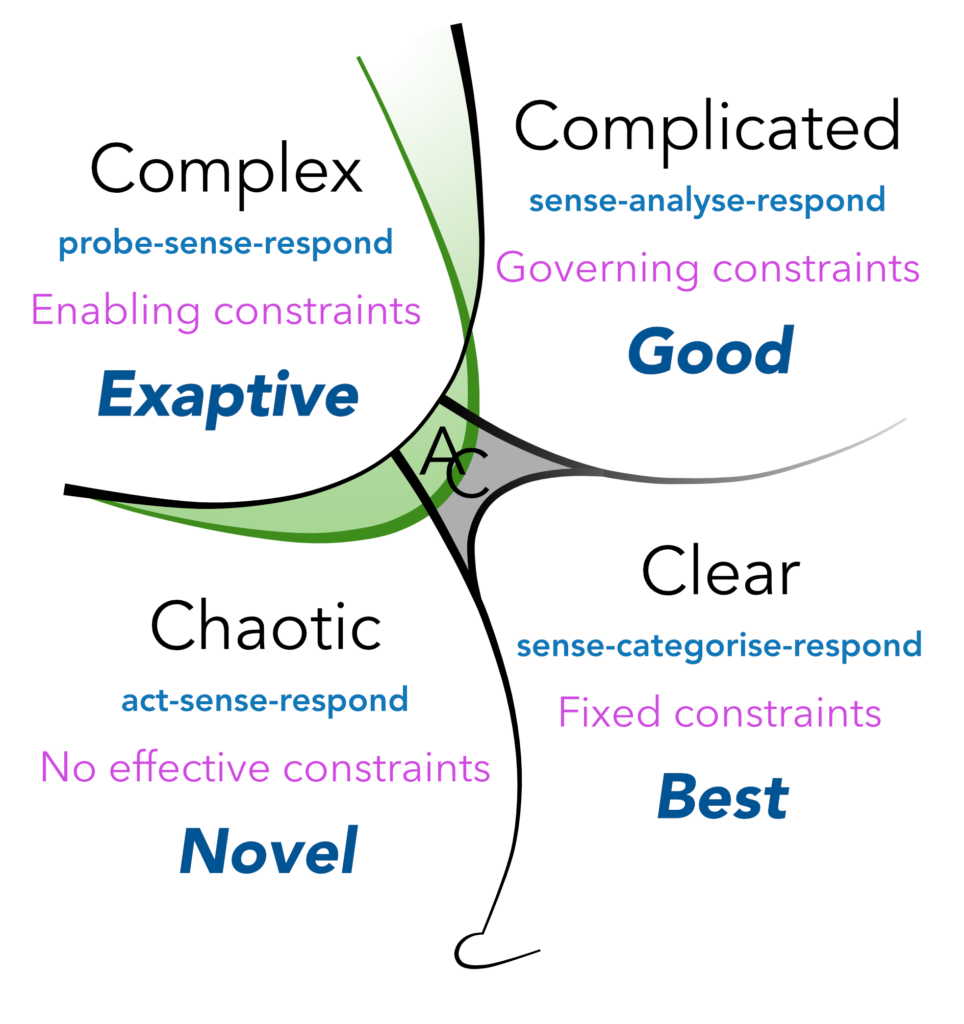

So the question is: When is putting ourselves in a position of not knowing useful? I would say it is always a good starting point as it gives us an open mind to sense what kind of situation we are facing and how the situation might be influenced by different contexts. The latest iteration of the Cynefin framework adds some very useful ideas and practices to this. First of all, the central domain of Cynefin has been renamed to Confused/Aporia. Confused means quite literally that we are not aware or do not care what kind of problem we are facing, which leads to all kinds of problems. Aporia, in contrast, means that we are putting ourselves consciously at a loss, into a position of not knowing, which allows us to approach a situation with an open mind. Dave Snowden describes a number of moves on how we can induce this aporetic state and also a number of pathways out of it. The essence of it is that it is always good to start from a place of not knowing, with a beginner’s mind and then decide whether best practice (the clear domain) or expert knowledge (the complicated domain) is useful or if we need to probe a situation to attempt to sense and shift patterns (the complex domain).

More to come … I still have a lot of questions around this. I’d appreciate if you could share some of your reflections this triggered in the comments below.

Featured image: cygnets on Bolam Lake (own photo)

Thank you for a refreshing article. I have followed Dave’s work and interacted with him on similar matters.

I have the view that a situation is complex because, for our purpose of considering the situation, it is beyond our cognitive capacity to understand at our level of tolerance for uncertainty. I adopt the agnostic view of knowledge – we must tolerate uncertainty to live, but we cannot claim certainty.

Your article resonates well. The majority of people appear to be uncomfortable with not knowing what is unknowable, so they fill the gap… the long silences are uncomfortable because of the anxiety of not knowing and being seen to not know. Over many years of leadership and leader development, anecdotally, I see this as all too common.

So, in my humble opinion, the A/C ‘domain’ is not distnguishable from the complex domain in a phase space. Of course, Dave has countered with his view. But I hold firm that, while A/C might be a valuable check for consultancy practices of reminding people not to assume they know, any position in a complex domain is one of a level aporia and confusion – otherwise it is, ‘for all our intents and purposes’, ordered (enough).

Once more, thank you.

Thank you for bringing this up. Beautifully written. I understand that the awareness of the value of not just accepting but consciously choosing the state of not knowing (although I like the word “aporia” very much it brings some connotations from its the origin in rhetoric which dye the central idea of puzzlement in specific colours) should come first and there will be more to discover and when and how to do so.

“That is not to say that structures are completely useless. ” — yes, I believe that the balance of “knowing” — “not knowing”, the tension “between creativity and the human condition”, in Steve Xoh words, is important. For me, it is a specific balance under the generic balance of Stability and Diversity (see https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/B08M5Y3HK7 ).

With this mind, the mere support of the of “not knowing” state, contains the balance for it can only be done from the position of knowing that not knowing is good.

Another association is with the pre-conceptual experience, advocated by phenomenologists, already from the Husserl’s introduction of epoché.

I work as a technician. I find that most men are constantly pretending they know what to do in a scenario even when you can see in their eyes that they don’t. However they do get through it (sometimes) and look like they do in fact know everything. Which perpetuates a dominant position of knowing and reliability. Whereas women tend to be less likely to take this position as it can be unsafe for others, or don’t feel the need to be consistently across everything all the time. Socially… this stems from constructs at play that enforce patriarchal structures. More men could definitely adapt this practice to even out they playing field for all in terms of equity.

Hi Marcus, I have a long answer as to what your article triggered.since I am also exploring what it means to me. curious what you think!

Why not knowing is essential.

Although I feel, understand and agree with what you are saying, I would want to challenge your perspective. The title. The disagreement I have with what you are saying would be one of nuance and perspective. I have a problem with not knowing as a value. It could easily be a prophecy on its own, a value in itself, a stepping stone for simplicity, not thinking or lazy thinking and more dangerously: disqualifying people who do think deeply and want to find things out and challenge the status quo. I would say that not knowing as the essential take away in dealing with complexity, is the opposite of the curiosity and exploration or to simply wonder.

Some basic assumptions first. 1: our reality is in essence inconceivable and inexhaustible; the complexity is limitless. 2: We need to make sense of the world to be able to act in it. We would disintegrate in this inconceivableness and inexhaustibility of the world around us without the ability to make sense (sensing discrepancies, equalities, identities, continuities/ changeability etc.) to be able to act (make predictions and intentional actions).

We would disintegrate or live in a state of continuous anxiety. John Searle writes about this in ‘the construction of social reality’ in terms of ‘direction of fit’ and ‘conditions of satisfaction’. It also relates what Pavlov describes in his experiment with the dog and the bell as a prediction of food to come. This ability to predict is not a prophetical super power but based on experience (including knowledge). Which means that some things are easier to predict than others. (the sun will rise tomorrow, or it will rain tomorrow)

If reality has an unlimited complexity than there is no end to philosophical and scientific reflections. This idea should/could relief us of the ambition to reach the top/ideal state and relief ourselves from the search for end goals and purpose and embrace the notion of progress.

This unlimited complexity implies that there are no meaningful answers to certain questions, some questions are fundamentally unanswerable. This to me is essential in dealing with complexity.

Especially questions on purpose: why are we here on earth? The notion of unlimited complexity is the starting point of reflection, we have to get some clarity to be able to move, but what that clarity is can not be established in advance. I think this is the unknowing you are referring to. But I would argue it is not the same, although maybe in nuance or perspective. Let me try to put my finger on it. It is not so much not knowing ( or letting go that the world is completely knowable) that is essential, but the exploring of what Nietzsche might call the pathos of knowing.( Nietzsche and the pathos of truth). Not knowing is not a blank slate that serves as a precondition for exploring what is possible.

In your article I would have put the emphasis on exploring, wandering and curiosity. And establishing clarity as a first step. Or, in dealing with complexity we have to embrace that science is never finished, that there will always be new knowledge, that we can always have new experiences…

But key to me are 2 things: 1. this is not so much an individual effort but collective one and 2. we can never get rid of ‘purpose’ like questions, or these unanswerable questions entirely, and therefore we cannot just embrace not knowing, or having that unknowing as a value/ essence in dealing with complexity. Because we are never free of context and collectivity.

To sum it up: let’s say that ‘knowing’ (from making sense to use to be able to act) goes through 3 phases.

1. Establishing clarity, establishing facts. Reflection is the starting point of exploration and it can only be done within certain boundaries/ markings of a terrain. The experiences of the past leave traces. These experiences and their traces are the discrepancies that need to be solved so we can make better predictions. They are traces Both in matter and in mind. These traces form the beginning to mark the terrain. Pieter Adriaans, a dutch Philosopher says; “Good philosophy is exploring previously inhabited terrains and map them. Science cultivates the terrains. Philosophy is therefor always simpler in nature than science. Philosophy is bringing potential fertility of the grounds to attention. It is exploring preconditions for science. In that sense it is more superficial than science. It doesn’t penetrate deeply in the structure of things, clarifying doesn’t measure things. But it is deeper than science because it plays with boundaries of that which could be scientifically explained”. In marking the terrain there are certain things that fall into the terrain and certain things that don’t. From memories to footprints, to waste, to pottery to letters and ruins. What we find is just a fragment (of what is left). What is lost is not in there to reflect upon. But things are inevitably lost. We often mistake what we find in there is the result of the boundaries. But If I look into my study of Ancient Egypt, mind and matter in the terrain, we have marked is a result of coincidence, the whims of the wind and time. what needed to be preserved at the time. but there is no ancient Egyptian left to turn to with an actual memory. We have some remains. Establishing the facts is the bases for further constructions. We select (the selected) order, arrange and determine. Some things are central other things are moved to the periphery, here we explore the boundaries as well. we establish facts and events and boundaries.

2. Constructing meaning: When the facts are established, we interpret them. This interpretation is done in a way of relating them. Recognizing cause and effect, comparisons, gradations, contradictions. These are also selections and combination processes. The truth test here is not about the actuality/ ‘equivalence of truth’ of the facts but on meaning giving as a ‘revealing’ truth. So were step 1 is more definite, step 2 is more subject of the discourse. (with the purpose to understand). To interpret means to understand and to judge at the same time. (this is the development stage of Searle’s status functions and systems of status functions) since they depend on collective acceptance and recognition. Collective acceptance and recognition are what you need to be able to understand and judge. Understanding is not judging and vice versa. To understand requires some form of collective recognition and acceptance to ‘identify’ a relation between the subject (gaining understanding) and the object we want to understand while judgement is about recognizing and accepting the line between the judging subject and object being judged. In terms of history: we try to understand human beings in their multitude actions and judge the actions at the same time. There is a big gap between potential and reality. For instance: even if we are born with the same depositions, we did not all become Nazis. Was Hitler a genius/ strong leader or a tyrant? This gap between potentiality and reality is a prelude to the next step

3. Employment, application and usability of the interpreted facts.

Historic facts are established, recognized as such, interpreted and now employed to realize new ideals. Their significance justifies actions, the system closes. The employment means: serving (of these values (understood and judged facts/events) the appreciation of the leading mode of thought/ existence/ ideal.

And that is the crux to the story.

Although these steps are in process sequential, they affect and influence each other. They are not free of the context and collective they are in. We have a reality we live in that is inconceivable and in exhaustible but within that reality our basic human experience is that of being born into a family, a community, a country and more distant ‘others’.

We are all born on some soil, under some stars, bound by climates, fates, science, luck etc. and we all experience being under the control of some sort of authority.

All these entities, (individual, family, community, others, authority etc) have the desire to answer questions that are fundamentally unanswerable. Be it in a sense of purpose or the desire to fulfill your potential, have an identity, being seen, or the idea that out of the existence of something follows the purpose or function or objective of the thing/ organism.

I think every religion, every Utopia, has the idea to ‘love thy neighbors’ or to love others.

And in every religion, belief or utopia ‘god’ reveals himself to those who love others. But

the perspective ‘to love thy neighbor’, the ideal of the good, is appreciated to the extend in which it leads to loving the leading god. And the same goes for knowing. The act of knowing/ knowledge is appreciated to the extend in which it serves/appreciates the leading ideal/ moral. Or to go back to Nietzsche, what we know as truth is what we have put into this world and moral is the sum of that truth “every closed system of the philosopher proves that within him one drift/ urge rules, that there is a fixed arrangement of things that calls itself truth. The feelings in accordance with that are: with this truth I stand on the height of ‘human beings’: the other is of a lesser kind, at least as knowable”. The ideal has solidified in one form. This is part of the making the circumstances useful to be able to act. Truth is not an object in reality but the correctness of logical thinking. Reality is brought in its desired state and then simplified. “For them peace is something like deep sleep”

The explorations, curiosity and creativity are never just a blank slate to find out what is possible.

It is never just embracing not knowing, it is in finding clarity as a value in itself and in testing/ breaking, questioning, exploring an underlying moral/ideal/ truth. and that is something that is essential in dealing with complexity.

I feel there is a window of opportunity for complexity thinking. The notion of complexity has forced itself upon us and is part of a trend that was going on already, that things are interconnected, holistic, context depended. This is an opportunity for people who find this interesting and are working with complexity to set the tone, introduce language or to support, facilitate and introduce complexity in action, its implications, possibilities and so on. Let’s not do that by talking of ‘not knowing’ as its essence.

Since one of the ‘faces of complexity’ right now are that of uncertainty and that of being at a loss.

That grieve, anxiety and mourning is not to be embraced by not knowing, but by the notion of eternal progress, curiosity and exploring possibilities in relation to the leading ideal.

The concept of endless complexity and never being able to know could also be an injunction to never stop thinking, which i think is the point.

This is a superb article both in terms of content, thinking and writing style.

I wondered, is your statement that “some neuroscientists even think that our brain only processes sensory inputs when they are different from what the brain predicted it would receive while ignoring the rest” inspired by the work of Surfing Uncertainty? Slate Star Codex recently wrote a superb summary (which you may well have seen, but in case: https://slatestarcodex.com/2017/09/05/book-review-surfing-uncertainty/)

On the broader issue of humans and our search / need for certainty (and hence ‘hatred’ of uncertainty), here’s some complexity inspired thoughts I captured – Three fundamental truths about uncertainty: https://www.richardhughesjones.com/uncertainty/

Hi Marcus,

thanks for your wonderful wirtten article!

I work as an art therapist with people in palliative situations. Usually we (all professionals) think they (patients & their families) have been told and know the state of progress of their onkological illness. But many patients seem to prefer not to know. Mostly it is a kind of psycholocial defense.

Today I saw a guest (male, 71). He is stil very active, volunteers at a garden community, enjoys travelling and staying in a lively contact with children & grandchildren – but now has a new progress. I asked him what he has in mind about the state of his progress and he told me very conscious he prefers not to know – also he is aware of a kind of unconscious pressure. He was very convincing telling me, that he feels more comfortable in not knowing, than in knowing. Knowing wouldn’t lead him anywhere, not knowing would open him.

Very hard to handle for the carers and doctors, but I loved it!

Hi Friederike. Thanks for you thoughtful comment and touching example. It’s a great example of how knowing often closes down options.

Hi Marcus,

Really enjoyed this article and the responses it elicited.

Thank you, Hans.