Systemic change has become a catch phrase in recent years, not only in the field of Market Systems Development. I have blogged about it before (for example here and here). The question I want to address in this post is how we can conceptualise systemic change as a first step in developing ‘Theories of Systemic Change’ and evaluating systemic change initiatives. And all of this in the face of complexity and unpredictability of how complex systems change.

A while back I blogged about a new framework for assessing systemic change that I developed for the Katalyst Project in Bangladesh (after this blog post we also published a paper on the framework). Since then, I have refined the framework, both as part of some work I did for another project in Bangladesh and partly to make it more coherent with my other work on complexity sensitive Theory of Change (this also needs to be updated, though). As I have not had the chance to publish the updated version in a paper yet (there is a plan …), I want to make it available on my blog.

Ok, let’s go then. Some theory first.

Complexity and emergence

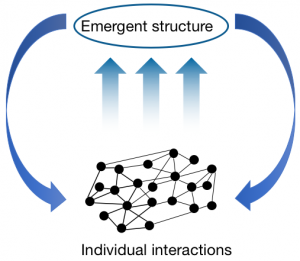

Figure 1: Stylised illustration of emergence in complex systems

Economies are complex adaptive systems, not machines. Complex adaptive systems are made up of a large number of interconnected actors who are continuously interacting with each other.

This interaction among the actors leads to the emergence of system-level structures and properties that cannot be observed on the level of an individual actor (upward arrows in Figure 1). These emergent properties are the reason for the saying that the whole of a system is more than the sum of its parts.

The emergent structure, in turn, influences the individuals by providing constraints on their behaviour (downward arrows in Figure 1).

A simple example of an emergent structure is a community, which can as a collective do more than the sum of what each individual can achieve. Yet, being part of a community means for an individual that there are certain norms about expected behaviour, not every behaviour is possible. This interdependency of behaviour and structure creates continuous dynamic adaptation.

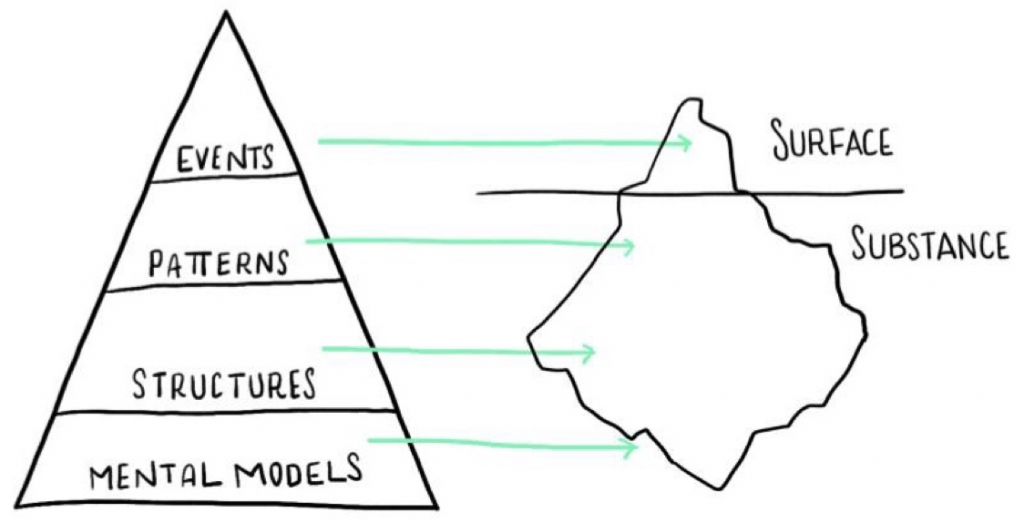

Figure 2: Conceptualisation of a complex system as pyramid or iceberg (Source: Leyla Acaroglu [1])

The pyramid shows the different levels that can be conceptualised in a complex system: events, behavioural patterns, structures and mental models or paradigms. The iceberg signifies that only the top-most of these levels is easily visible and observable, while most of the levels lie under the surface.

While causality in complex systems is not predictable, the emergent structures show a level of stability that can be used to determine a system’s disposition, i.e. it’s inherent qualities, and its propensity for change. In other words, understanding these system characteristics allows us to say in which way a system is more likely to change – and out of possible change directions we can determine which one we like most. Over time, we can observe how this disposition changes.

The structure of a complex system can be described by using two key concepts: attractors and constraints. A third important concept in complex systems is diversity and redundancy.

Attractors

- Attractors embody a set of coherent values and beliefs – for example a religious tradition acts as a complex attractor

- They encode specific behavioural norms – for example how to behave on a busy intersection in traffic

- Attractors modulate how new information is processed – for example the way information on scientific evidence for climate change is interpreted by climate change skeptics

Constraints

- Constraints can be governing or enabling – they can prescribe a specific behaviour through a rule or they can enable a behaviour by connecting different actors, for example through kinship

- Constraints define what is possible or perceived to be possible – or enable things to become possible

- Constraints can be physical or social boundaries, for example transparent walls or cultural taboos

Diversity and redundancy

- Redundancy provides an ‘insurance’ if some components fail – as seen for example in the internet, that still functions if some routers fail

- Diversity ensures that components react differently to disturbances – for example different species react differently to human pressure on their habitat

- Maintaining diversity and redundancy is a basic principle of resilience

The systemic change framework

A change initiative can change constraints, catalyse attractors or manage diversity and redundancy within a system. It can achieve three things with that: move an attractor regime closer to a desired state (incremental), achieve a tipping point to a new attractor regime (catalytic), or manage diversity and redundancy to increase resilience.

It is important here to remember that systemic change does not happen through the scaling of one single innovation in a system. Rather, it happens when many changes come together over time, interacting with and building on each other, in order for the system to evolve. Consequently, a change initiative should work with a portfolio of interventions, which can be grouped into categories of enablers of systemic change (I’m not sure if ‘enabler’ will be the final term, but for the moment I have not found anything more fitting – suggestions welcome).

The Systemic Change Framework

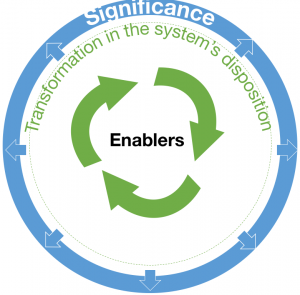

Now, to conceptualise systemic change, one needs to ask three questions:

- Which categories of enablers for systemic change is the change initiative influencing or catalysing? What else is changing?

- How is the disposition of the system transforming?

- Is the change significant?

This gives us three elements for a framework: enablers, transformation and significance. Enablers are of course not only the ones the change initiative is influencing – there are many enablers and disablers out there the initiative is not actively working on but they are still important influencers in the systems – this is what makes these systems complex and unpredictable.

The significance of the transformation is important to understand. Significance can be defined in different ways depending on the context. One way to look at it is that the transformation in a system’s disposition needs to reach a critical mass. If too small a part of the system has gone through the transformation, the risk is big that the pressures from the environment will force that part of the system to revert to an earlier state. For example if only one municipality adopts a new way of doing things, the pressure from the higher levels of administration to fall back in line with the other municipalities might reverse the change. Or if only the producers in a value chain introduce some change practices, the downstream actors might use their power to revert the practices to an earlier stage.

Another way to look at significance is to understand how ‘deep’ the transformation is going (think iceberg). Are we mainly looking changes in behavioural patterns? Or changes in structures like institutions and norms? Or are we even looking at changes in the mental models and paradigm of the people in the system?

Measuring Systemic Change

Measuring systemic change is then done following these steps:

- Define indications of change for each category of enablers (how would the new situation look like?)

- Define how to assess transformations in the disposition by mapping attractors and constraints and assessing diversity

- Find appropriate methods and tools to observe and measure these changes

- Keep looking for unintended changes or changes caused by other influencing factors

How to build the conceptual framework of systemic change into a theory of systemic change will be the topic of a next blog post.

References

[1] Tools for Systems Thinkers. A series of blog posts by Leyla Acaroglu (link to first article).

Thanks Marcus for this nice blog post. One reality you mentioned makes me think: “It is important here to remember that systemic change does not happen through the scaling of one single innovation in a system. Rather, it happens when many changes come together over time, interacting with and building on each other….” This means also that development work has to be very careful in thinking about the change opportunity of one project in a context of a rather low shift in other societal activities. This means to me also that work of development and change initiatives in traditional contexts, where other additional changes are rather not happening, it is very difficult to change attractors ins such a reality. A last and maybe a bit provocative question then comes into my mind: Is it really realistic to promote an effective change via projects?

Thanks for this clear presentation.

Best, Frank

I am finding the difference between attractors and constraints very blurry. For example religious values or knowing what to do at a traffic crossing also “define what is possible or perceived to be possible – or enable things to become possible”.

Hi Bhav. Thanks for your comment. I agree with you and I have been struggling with this as well. Maybe it is more a question of using different perspectives on (or metaphors for) the same thing than it is about categorising things to be either a constraint or an attractor. Attractors are useful when we look at a landscape and understand what are the predominant ways things are done. Constraints can be useful when we look at specific practices and also when we think about intervening in a complex system as we can manage some of the constraints. An attractor landscape can help us understand a system’s disposition for change – where is change likely and where not. Constraints can help us understand the trajectory or propensity for change – how the change might look like. But I would love to hear your take on it. What do you use in your work and what is useful for you?