In 2013, Richard Hummelbrunner and Harry Jones asked: “How can policy makers, managers and practitioners best plan in the face of complexity?”

Seven years later the search for answers to that question continues through different initiatives and programmes. For example, the Doing Development Differently Manifesto was published at the end of 2014. Matt Andrews and his colleagues at the Building State Capability program launched a successful online course on Problem Driven Iterative Adaptation and published a book in 2017. David Booth has written extensively about the adaptive and iterative approach of the Coalitions For Change programme of The Asia Foundation in The Philippines.

So, where are we in this discussion? What are the challenges around transitioning ideas from complexity into projects and programmes? To answer these questions I have reached out to Arnaldo Pellini, founder of Capability, to hear about his experiences working with development initiatives and discuss some of the open questions we are yet to answer.

Marcus Jenal – I often work with projects that face intractable or messy development challenges. They try to analyse the situation to a point where they hope to find a single way forward – which they never hit – so they get stuck. They have an expectation that they will find the right answer, while in reality that answer might not exist. When I collaborate with these projects, instead of doing further analysis I engage with them to help them make sense of what they already know and turn this into ideas on how to move forward from where they are – rather than to fantasise about an ideal future state. The principle behind this is that in complex and uncertain contexts you cannot get answers through analysis, you only understand the situation if you engage with it.

Let’s talk a bit more about this idea of sensemaking. Have you come across it in your work, Arnaldo?

Arnaldo Pellini – I recently came across a method that tries to do that. It has been adapted by the UNDP Accelerator Labs and they call it Sensemaking Protocol. These Labs emerged from the recognition that the complexity of the social and economic problems we face today cannot be addressed using a traditional, linear, planning and implementation approach. The Labs are being established in various countries and are meant to support UNDP country offices with advisory services. They support testing and experimentation in their programmes and projects. The Labs use sensemaking as a facilitation and reflection method to help country teams capture learning from different initiatives and assess the coherence of the portfolio of projects they implement. It is a remarkable experiment which will test the flexibility of the UNDP systems.

Have you come across sensemaking as an approach to deal with complexity? What do you think about it?

Marcus Jenal – I have. For me sensemaking is about reflecting on how to act based on limited knowledge about the context we find ourselves in. Dave Snowden makes an important point in saying that not all contexts are the same and the way we act needs to be adapted to the context. He developed the Cynefin Framework to enable us to identify the kind of systems we are dealing with and suggests the appropriate strategy to respond. For example, in an ordered context where cause and effect are stable and determinable, we can analyse a situation and find a right way of doing something – like finding a way to send a person to the moon. Once we figured out how this works, we can define it as good or even best practice and prescribe it. In a complex context, however, understanding the past does not help us understand the future. This means we have to come up with solutions as we go. The sequence of analysing-planning-implementing-evaluating does not work here. We have to do it all at the same time. The strategy here is to probe the system by using a portfolio of safe-to-fail experiments and make sense of what we observe as a consequence.

Sensemaking helps us determine how to act based on what we perceive (or sense). It is about finding ways forward in initiatives that find themselves trying to solve uncertain and complex problems. But different people make sense in different ways and come to different conclusions, as there is no one right way to act in complex contexts – there is no good or best practice.

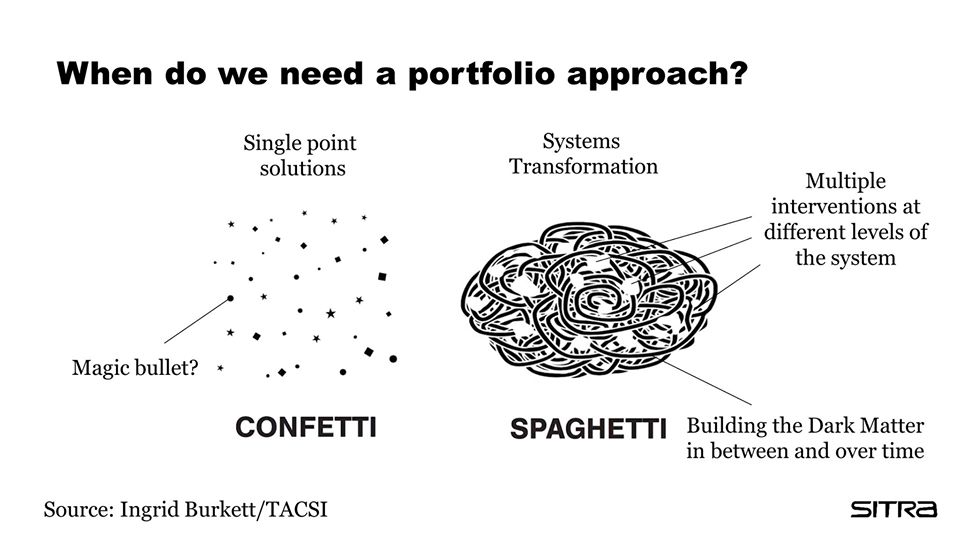

Which brings us to another important concept – using a portfolio approach. Instead of trying to find alignment in the involved group of people, we can create a portfolio of different experiments and test which hypotheses work, using the diversity of perspectives as an asset.

Have you had any experience using a portfolio approach?

Arnaldo Pellini – Not in the way you describe it. I have been involved in large programmes where different components were managed as individual projects. However, at the end of January, I went to Helsinki to participate in a two-day workshop organised by the Finnish Innovation Fund, SITRA, on innovation portfolio management and sensemaking. One of the organisers, Mikael Seppälä, explained the rationale for the workshop as “perhaps the barrier hindering us making a better global or societal impact is not the lack of ideas and projects but rather in their relationships to each other”. As you said, Marcus, we know that experimentation, given the uncertainty of finding solutions to complex social problems, is useful. But a set of experiments run in parallel, without coherence, is just a set of experiments. It is not a portfolio – which requires some level of strategic coherence. At the workshop, Tom Mitchell of Climate-KIC gave the following definition of portfolios of experiments: “Connected innovations that learn from each other. A deliberate set of connected experiments.” The key word here is, connected.

A connected portfolio of experiments can help find solutions to complex problems because it allows different perspectives and (contradicting) hypotheses to be tested. Moreover, it can stimulate reactions from partners and stakeholders about what works and what does not and focus resources on solutions that are gaining traction.

Managing a portfolio involves investing time and resources in extracting learning, and assessing the coherence within a programme and project. This can be done when teams move a step up from their day-to-day tasks and observe the programme or project from above – which brings us back to the need for regular sensemaking. This is easier said than done.

One problem is that programmes and projects that have the ambition of being adaptive and flexible, at the end of the day are asked to produce annual plans and budgets with detailed information about activities and deliverables, which can limit flexibility. A second problem is that when programmes manage to design a set of experiments and be responsive to their partners’ needs, they end up being too stretched and struggle to develop a coherent narrative about their strategy. So, the questions I have are: How can a project be adaptive, flexible, etc. and at the same time maintain coherence across activities and experiments? Is there a way to assess the extent to which programmes are flexible, adaptive, and importantly, coherent?

Marcus Jenal – The traditional approach would be to define a logical sequence of how we expect change to happen and then to define indicators that show us how we are progressing along that logical pathway. Now, if we are dealing with complexity, this approach does not work, as we cannot define causality in advance – remember, complex systems are unpredictable. What we can do, however, is for each experiment in a portfolio describe in clear words what success and failure looks like. We can either use abstract descriptions of success or, better, we can use narratives that exemplify positive and negative change – enabling us to say “we want more stories like this one and less stories like that”. This gives us a clear sense of direction. Snowden calls this a ‘vector-based theory of change’, as it defines with direction but without defining the exact path. At Mesopartner we call it a ‘strategic intent’ – which is exactly what we need to find the necessary level of coherence in a project or programme. It is not an ideal future state, like the government implementing a number of very specific pieces of legislation nor a specific target like creating 1,000 new jobs. Rather it acts as a compass that helps in the sensemaking process: What is the right direction to move in?

To measure change we need short feedback loops that are able to capture weak signals of change and allow us to respond quickly. If we use logical cause-and-effect chains we are biased by how we imagine change to happen. And if we only use measurable indicators, we are biased towards the things we can measure. We need to also use other ways of sensing change, from simple observations to detecting changing patterns in the narratives people tell each other. At the same time, we cannot only look at our imagined patterns of success and failure. We also need to keep an eye on the overall situation in order to catch unexpected changes as a result of our experiments. So sensemaking is not only about how to move forward; importantly it is also about observing which experiments have which effect, and determining what that means.

But what are the tools and methods that we can use for sensemaking?

Arnaldo Pellini – At the workshop in Helsinki we role-played a sensemaking process. It included two exercises based on a fictional urban planning and climate change case. The first exercise was about portfolio composition: eight people had to pitch a project idea in three minutes. Only six projects could be selected by a review team. The main criteria for selection were the links and connections between the set of projects (i.e. the connectedness). The second exercise was a mini sensemaking workshop where the six projects reported to the group about progress, results, and challenges they faced a year into implementation. They presented to the larger group and answered their questions. In the meantime, three people (i.e. observers) were taking notes about the discussion from different angles or viewpoints: the social value of the projects, the external factors influencing the projects, the links between the projects. We then walked around the room to listen to their notes and key takeaways, and their ideas on how to make sense of the changes that the portfolio of projects was contributing to in urban planning, as well as measures to reduce the impact of climate change.

Marcus Jenal – A very simple tool that we often use in our practice is called STICC, developed by Gary Klein. It is a simple format for a team reflection meeting with a clear orientation towards sensemaking and action. Here’s the logic. Each person presents their situation using the following sequence, speaking from their own perspective:

- Situation: Here is what I think we face

- Task: Here is what I think we should do

- Intent: Here is why I think this is what we should do

- Concerns: Here is what we should keep our eye on: these are risks we might face.

Now the other people in the room join in and engage in the discussion:

- Calibration:

- Tell me what you don’t understand

- Tell me if you can’t do it

- Tell me if you see something I don’t

- Tell me if you see it the same way

This leads to a lively discussion bringing in different perspectives while always focusing on the task at hand. The tasks that are suggested by the team members can, once calibration is done, be taken together into a portfolio, for example. The aim of the exercise is not to achieve alignment among the people in the room, but to improve the coherence of each task and the overall portfolio. There can and should be dissenting views if we act on a complex problem. The portfolio approach allows us to test these diverse views and see which one can get more positive traction.

All this is very interesting, but one question we have been grappling with is: How do we bring the idea of portfolio approaches more into our work in international development?

Arnaldo Pellini – I grapple with a similar question. Outside the international community of practitioners, managers and researchers who discuss and who are passionate about bringing complexity thinking into the design and implementation of projects and programmes, is there a real demand for this way of thinking and working within development partners, government partners, etc.? Some people are very excited about what all this can bring (the sensemaking workshop sent an electric shock through the numb chords of our professional spines), but how large is this community and is it growing? Let’s see what the readers of our blog conversation have to say.

I’m happy for you to repost this blog article – just let me know. And please add this text if you repost this article on your platform or blog: This article is republished from Marcus Jenal’s blog under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article here.