In this post I want to share with you an idea of a new conceptual framework for monitoring and results measurement (MRM) in market system development projects. To manage your expectations, I will not present a finished new framework, but a model I have been pondering with for a while. The model is still in an early state but it would be great to harness your feedback to further improve on it. Indeed, what is presented here is based on everything I have learned in recent years from a large number of practitioners that contributed to the discussion on Systemic M&E, my work in the field, but particularly also from the guest contributions here on my blog by Aly Miehlbradt and Daniel Ticehurst and the intense discussions on MaFI. The ideas are strongly based on the learning from the Systemic M&E Initiative and also apply the seven principles of Systemic M&E, although I am not doing this explicitly.

Theory vs. hypothesis

There is a need to differentiate between a theory of change and a hypothesis of change. According to Wikipedia, theory is a contemplative and rational type of abstract or generalizing thinking, or the results of such thinking. I underlined two words that seem important to me, i.e. abstract or generalizing. Hence, a theory is not context specific. In contrast, a hypothesis is defined as a proposed explanation for a phenomenon. A phenomenon often is context specific. Context specificity is only one way to differentiate between theory and hypothesis. In the text on wikipedia, another explanation is used: “A scientific hypothesis is a proposed explanation of a phenomenon which still has to be rigorously tested. In contrast, a scientific theory has undergone extensive testing and is generally accepted to be the accurate explanation behind an observation.”

Looking at these definitions, I suggest that in our work in change projects, we are actually using hypotheses of change, rather than theories of change. These hypotheses are, of course, based on some sort of theory that is behind our expectations of the outcomes and impacts of the project. But it is also based on a lot of assumptions that are embedded in the history of the system and that are informing not only our but also key player’s decisions. Hence, what the individual project should work with is a context specific hypothesis that needs to be tested. Based on this testing, projects can then feed back the generalizable part of their work into theory. This theory can be used by other projects to inform their specific hypothesis of change.

To test a hypothesis of change and whether it leads to an improvement of the situation is in my view the most important aim of a development project. A consequence of this is that the monitoring part of the project needs to be as important as the implementation part. As only with solid monitoring can we gather enough information to prove that our hypothesis was indeed correct – or alternatively to falsify the hypothesis and come up with a better informed version.

How we think change will happen — our hypothesis of change

“Theory based” approaches have been recognized by many as important starting points for results oriented projects. Following my little excursion above, I would tweak this a little and say that projects need to be based on clear hypotheses. The hypotheses should not only include what we think could happen, but also express on what assumptions this is based. I use the plural hypotheses here very consciously, as the multitude of perspectives both within the project staff but especially also when having other stakeholders participate, will not allow us to condense everything into one single hypothesis of change. This is not a bad thing. On the contrary, a variety of hypotheses followed by a variation in piloting interventions makes our project more likely to find the interventions that work. The convergence on a single hypothesis is extremely limiting the degrees of freedom and innovation of a project.

The aim of formulating hypotheses of change is to gain clarity about the situation, our current understanding of it, and the way forward. Hypothesizing is important as it gives orientation to the analysis and helps to better define gaps in information and understanding. A hypothesis is formulated informed by practical experience (things seen elsewhere), underlying knowledge as well as personal preferences. Hypothesizing, hence, reveals bias, beliefs and assumptions of the members of the team, making the their understanding of the system under investigation explicit. It helps the team to become aware of its own perspectives on the situation and most importantly also its own biases.

How change progresses — waves of change

Many practitioners express that the use of causal models that connects a project’s activities with the intended outcome (or in general even impact) is very helpful for them to make the succession of change they imagine explicit. Causal models enable the project to be explicit about what they do and why, guide discussions within the project team, and with donors and project partners. Causal models are most often expressed in the form of results chains, as these are promoted for example by the DCED Standard for results measurement as good practice. Usually, they are also accompanied by a logframe that condenses the logical succession into a format that is accessible by bureaucrats in head offices.

Still, these types of causal models are also criticized – and I for my part am very skeptical about them. There are various problems. To name just two, the design of detailed causal models can, firstly, lead to a premature selection of one solution that makes sense to the donors and NGOs. This is done at the expense of solutions that make sense to the stakeholders, which require processes of participation, convergence and co-creation. Secondly, the complexity of the situations eludes the capacity of project teams or also stakeholders to accurately understand the dynamics and derive a logical, linear intervention strategy and all its possible consequences on the system. Not only this, but as we are working in complex systems, the exact way how change is going to unfold is not predictable (for the full discussion of pros and cons of causal models, see our Synthesis paper on the Systemic M&E Initiative).

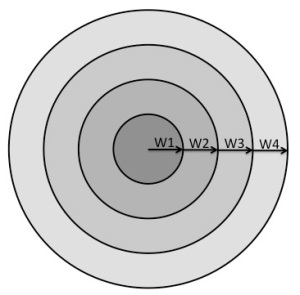

As outlined in my earlier post, a new perspective on causality is needed that is based on insights from complex systems research. The main lessons there are that we cannot predict causal succession and that we can only contribute to or catalyze change, not cause it on our own. Still, complex systems are not chaotic but can contain relatively stable patterns. Hence, I propose a model that is not based on clearly defined chains of causality but focuses on the succession of typical patterns of changes that we expect. We can define generalized patterns that seem to be part of such change processes, as seen in other economic development initiatives. I call these repeating patterns waves of change. The metaphor I am using is the ripple of waves that a stone causes when thrown into a pond. Of course reality is not as smooth as a quiet pond. I rather see a very dynamic piece of water where the ripples are strongly influenced and formed by the already existing waves. Depending on where and when we through the stone, the future will unfold on completely different ways. In some cases, the emerging patterns might actually be different than the ones we predicted. Thus, we also need to be open to that, be able to recognize it, and adapt accordingly.

The Waves of Change model

The waves of change are based on the principle of network driven change as described in the Systemic M&E Synthesis paper. It is also strongly inspired by work of my friend and co-author of the synthesis paper Lucho Osorio. The waves of change are also recognized in current practice. Most results chains are based on a succession from input to project activity to market trigger, market uptake, and systemic change. The problem here is that by formalizing these successions into detailed, step by step causal chains, we try to predict an exact succession of detailed change processes that are not predictable as such. The waves of change model offers a more open and flexible way of imagining the succession of change. This allows openness to harvest creative change that emerges from our interaction with the system but could not have been predicted.

Each wave contains a typical, generic pattern of change that is expected in typical interventions.

- Wave 1: Change at the level of the collaborator, i.e. the actor the project has direct interaction with. This wave contains the actual output of the project, like presentation and negotiations around improved business models, demonstration activities, the brokering of new connections between market actors, etc.

- Wave 2: This represents the buy-in of the collaborator and the mobilization of his own resources. Here the project can still play a role, for example in co-funding certain activities like the training of the collaborators network of agents. In this wave, we expect to observe changes in the strategy of the collaborator, e.g. by changing business plans, investment plans, distribution models, shift of resources, changing use of human resources, etc.

- Wave 3: In the third wave we want to see changes in the counterparts of our collaborator and his network, i.e. his clients or suppliers. This can mean the adoption of new production technologies or the increased purchase of inputs at farmer level, the application of new quality standards on manufacturer level, etc. Where these changes can be observed depends strongly on the type of system we engage with (agricultural sector, manufacturing, knowledge sector, etc.). Wave 3 touches upon the wider system, outside the influence of the project. Change here is driven by the market actors themselves and influenced by a wide range of factors in the system. The project does not play any role.

It is only once this changed behavior spills over to other competitors or affects the behavior of other actors in the system that the broader system is affected. For this change to become visible other competitors have to receive signals that there is a new or different way of doing things, or that better results can be achieved through the use of specific knowledge. It is hard to predict which change in behavior at the firm level may trigger a change of performance of the broader system.

- Wave 4: Here we want to see that the change is indeed adopted by the wider system and spreading beyond the project’s collaborator and his direct sphere of influence. This can mean that the improved business models are copied by other actors on the same level or other forms of crowding-in happen. This can also mean that policies are adapted to enable the new business models to work or that new coalitions and networks are formed between market actors.

Based on these generic patterns or waves of change (i.e. the theory), the project can develop its specific hypotheses of change adapted to its unique situation and context. Instead of directly linking activity with steps of change through a fixed arrow (i.e. a results chain), the team can discuss how, when and where they assume change will happen. This leads to areas of observation in the different waves. Expected change in these areas can be used to define ways of capturing the change. Besides the change that we are anticipating, we also need to look for externalities, positive or negative. That means that we need to broaden our view beyond the change we anticipate and be open for other things to happen.

This model also allows to integrate learning by adapting it over time. It does not have to be completely filled in the beginning. Indeed, a project might start by only filling Wave 1 and maybe Wave 2. With this, the monitoring framework can co-evolve with the project and the understanding of the project team of the system. The model also allows for multiple perspective on change. Different hypotheses and strategies can be run in parallel and compared based on their effectiveness during a pilot phase. This allows the project to use an evolutionary and experimental approach, which is also implemented in the monitoring system itself.

Once we start observing the real system, we cannot only reflect back on the hypothesis, but even go as far and question the theory behind it and redefine the waves of change. Hence, this framework is very flexible and open to learning and adaptation.

Who is responsible for impact level measurement?

Now where does the poor beneficiary population come into the picture here? In the theory, the changes at the level of the beneficiary happens in Wave 3, where the beneficiary population is expected to adopt the innovation introduced by the project and its collaborators. Being poverty reduction projects, it is expected that these innovations, once adopted by all market actors, are actually leading to the intended impact. This, however, opens a whole new can of worms and field of discussion. Does the project have to prove that this is actually happening or is it enough if the project infers impact based on theoretical knowledge? Is it, indeed, the responsibility of every individual project to prove again the link between outcome and impact? These questions need to be discussed.

Concluding thoughts

One might argue that leaving the results chains with their nicely linked boxes will make it more difficult to attribute change to one intervention. But to be honest, just because you draw an arrow between two events does not mean that the one causes the other. This is where the new perspective of causality comes into play. In complex systems, there are always various elements that need to be in sync for a specific change to happen. What contribution can be attributed to the project? Maybe it was just at the right time at the right place talking to the right people? There are also more discussions needed on how we can approach the questions around attribution or contribution, especially if and how they can be quantified.

Another open question is the need to stimulate and measure resilience in a given system. Following the principle of sustainability as adaptability, the goal of the project should not be to drive the adoption of one specific solution. Rather, it should foster the solution seeking capabilities of the actors and the system. It needs to be discussed how this can be integrated into the waves of change model.

More work and thinking is needed to craft out the different waves of change, describe them in more detail, and even develop examples of indicators that can be used. We need to develop tools to capture the change that go beyond the collection of indicators. They could for example be based on narrative sensemaking techniques. I am sure a lot of work is already done that can be adapted into this model.

Questions that need to be addressed by every project team when developing their hypothesis of change — could include the following:

- What (types of) interventions are planned?

- What is the direction the system needs to evolve in?

- What are our own assumptions now about the system, what is causing its current behavior?

- What is the systemic change that will lead to the the change in the evolutionary pathway of the system?

- Mechanism of the change: What level of the system is targeted, how is the landscape of constraints being changed/modulated?

- Observation areas: Where is change expected to happen, what is the extent of change that is expected, what are expected spillover effects?

- Progress of change: how is the change intended to progress through the system from the activities of the project with partners to the systemic change intended? Who are the change agents and how are they connected to each other? How can the spread of change be supported?

- Networks (strongly connected and partly overlapping to the point above): How are we using networks to achieve change? How are we building networks?

- Externalities: What are possible positive and negative externalities?

I am very curious about your reaction to this proposed model of waves of change. Please use the comment box or contact me directly (contact form / LinkedIn profile).