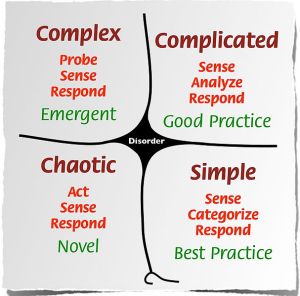

The last week of June I had the privilege of attending a three-day training event with Dave Snowden, founder of Cognitive Edge and “mental father” of the Cynefin framework. For me this was a great experience and although I had read a lot of stuff around complexity (also by Dave), there were still many new insights I got. Some things were new, others just became clearer. One thing that I knew but that was becoming more pronounced during the training is the differentiation between best/good practice and emergent practice.

The last week of June I had the privilege of attending a three-day training event with Dave Snowden, founder of Cognitive Edge and “mental father” of the Cynefin framework. For me this was a great experience and although I had read a lot of stuff around complexity (also by Dave), there were still many new insights I got. Some things were new, others just became clearer. One thing that I knew but that was becoming more pronounced during the training is the differentiation between best/good practice and emergent practice.

In the ordered domains on the right side of the Cynefin framework, cause-and-effect relationships are clear, if also in the case of the complicated domain not necessarily obvious. Cause-and-effect relationships don’t shift and we can always expect the same result when we do the same thing. This is why in these domains, we can do results based planning and management. We can define the results we want to achieve and develop a way to get there. In the simple case, there is one obvious right solution, the best practice. In the complicated case, there might be multiple ways to achieve the intended results and we might have to employ analysis or experts to find them. But once we have them, they always work. This is what we then call good practice.

In the complex domain, cause-and-effect relationships are not fixed and only discernible in hindsight – and even then we cannot be sure what really caused a specific change, it’s often a combination of things that play together in a unique way. We cannot predict how the system is going to react to a specific intervention. We often don’t have a clear idea about the problem (symptoms, causes, root causes, etc.), nor do we have a clear and unambiguous idea what a good result would look like – there are multiple perspectives on that. Additionally, we often do not have the necessary evidence to base our decisions on but have to use rules of thumb or base our decisions hunches. Thus, it becomes difficult to plan for a specific result. What we can do in this situation is to manage a project in a way so that it stimulates patterns to emerge in the system. We can then dampen patterns that we don’t like and stimulate patterns that we like. This is then called emergent practice, as these solutions fully emerge out of the context and are, hence, adapted to it. Solutions that emerge out of the context on the one hand work better than the ones that are imposed from the outside and on the other hand can lead to results that we could not have imagined before. A consequence of the strong context specificity of complex systems is that we cannot copy best or even good practice from another system, use in our system and expect it to work.

What are the consequences for our work in economic development? What I can observe in many (if not most) projects is that the project team has a relatively clear idea on how the solution looks like – an improved business plan, the adoption of a new technology, etc. This is usually good practice that they observed somewhere else or that was described in the literature. The project then selects a number of collaborators such as lead firms within a value chain to introduce these good practices. This most of the time is a rather intensive process including a lot of training of the collaborator and its partners. In many cases, the good practice is somehow adapted to the local context, but it is still always driven by the idea about an idealized future where this technology or business practice is applied. Once the collaborators have implemented the good practice – often successful, as they got a lot of help from the project – we expect that other market actors “crowd in” and copy the technology or improved business practice. This is were many projects get disappointed. Copying happens only slowly or not at all. Looking at the intense support the project gave to the early adopters, this comes, however, not as a surprise. Instead of allowing a local solution to emerge based on the current capacities and capabilities of the system actors, the project introduced a ‘good practice’ that is not necessarily adapted to the local capabilities. Other actors might see that the one chosen company does better, but they don’t know how to adopt this because it has not emerged out of what is available there in the system, accessible by all the actors.

One of the cons of this diffusion of innovation approach is that the communication process involved is a one-way flow of information. The sender of the message has a goal to persuade the receiver, and there is little to no dialogue. The person implementing the change controls the direction and outcome of the campaign. In some cases, this is the best approach, but other cases require a more participatory approach. Another critical problem is that we merely help the actors to become robust and path dependent. They cannot adjust their equipment because it was not developed by them. The whole ecosystem is ignored.

This does not say that it is hopeless to introduce new technologies or stimulate innovation in a given context. But the approach needs to be different. Innovation cannot be driven from the outside, but needs to emerge from among the system actors based on what is already there. This does not mean that they cannot adopt a new technology from somewhere else, but it needs to be within reach of the actors, they need to be capable of handling it. An innovation systems approach focuses on the environment and how conducive it is for firms/farmers to solve their own problems individually, collectively or through cooperating with a technology intermediary (read more about innovation systems here and find a series of blog posts on innovation systems by Shawn Cunningham here).

This is actually supported on a macro level by César Hidalgo and colleagues who analyzed products produced by different countries and the relatedness among these products and with production factors in the countries. They built a network based on the relatedness of products calling it the “product space.” In the abstract of their Science Magazine article, they write

Empirically, countries move through the product space by developing goods close to those they currently produce.

Here we see the same phenomenon that most countries – despite the big amounts of aid money that is flowing into economic development – only advance slowly. An improved version of economic development should, hence, not try harder to impose what we perceive as ‘good practice’, but support policies that lead to emergent practices that allow these countries to make larger steps in the product space towards its core, where the developed countries are. Hidalgo et al. write:

Most countries can reach the core only by traversing empirically infrequent distances, which may help explain why poor countries have trouble developing more competitive exports and fail to converge to the income levels of rich countries.

Hence, it is not to say that it is hopeless because we can only build on existing capacities instead of “bringing innovation”. On the contrary, we will get nowhere if we ignore existing capacities and the system around them. We need to find a way to build on existing capacities and enable the local economies to make faster progress for example by adopting an innovation systems approach. To conclude with the words of Hidalgo et al:

It is quite difficult for production to shift to products far away in the space, and therefore policies to promote large jumps are more challenging. Yet it is precisely these long jumps that generate subsequent structural transformation, convergence, and growth.

Marcus

Great stuff.

A question for you. Where would you position initiatives like the New Alliance for African Agriculture (large scale farming projects driven to a large extent by western private sector companies) and the more general push to incorporate smallholder farmers into the supply chains of global companies. Is there a fundamental contradiction between these approaches – which now get a huge amount of attention and which seem to be based on ‘bringing’ a model of development – and the principles of emergence and the innovation systems approach or is it possible to envisage a way in which they can be brought together?

Hi John. I do not really know the details of the initiative you mentioned. I would say that in principle the same idea applies. Of course you can to a certain extent bulldoze a system if you are big enough and just impose your idea. But I could imagine that the risk that this will actually end in chaos rather than in a big success is significant. Only think about the whole land grabbing debate – which would kind of go into the direction of western private sector coming in to do large scale farming projects. There is a high potential that this will eventually lead to unrest and chaos.

Again, one thing that I want to stress it that I do not say that you cannot introduce any new ideas into a system. The point really is that the system needs to be able to absorb this idea and make it its own. I see our role very much as facilitators that enable the systems we work in to innovate, to create new technologies, business models and products. If we focus on what we know and what we can bring, our focus remains very narrow. The solutions co-created in these systems can be radically different from what we could imagine or what we could offer to them and still work better. I write co-created because I do see a role for development agents to facilitate this process. To find solutions that we could not even have imagined really is the strength of searching for emerging practices.

Pingback: A Complex Thing! Are measures of complexity an end in themselves to address extreme poverty? | OECD Insights Blog