In my last post, I wrote about why institutions matter for economic development. I also highlighted that the theories of institutional economics and of complex systems actually come to very similar conclusions about how institutional structures, underpinned by basic beliefs or paradigms of how the world works, shape relatively persistent patterns of behaviour, which can be both beneficial for, or holding back development. In this post, I want to share a model that describes the dynamics of institutional change. It is largely based on Douglas North’s book ‘Understanding the Process of Economic Change’ [1], but uses the systems iceberg as a canvas. If you haven’t read my last post, I recommend you head over there and read that one first.

First I want to make two disclaimers. The model I’m going to share here is a stark simplification of reality. Yet, I think it is simplified in a way that the process described is still coherent with the underlying theory of institutional change and complexity and more details can be added to it as the understanding of the people who use it grows – in a way it represents the first principles with regards to institutional change that are valid in all social contexts. When I talk to people who have studied this process, they always say things like: “yes, but here you also need to say that …” or “can you not add the aspect that …”. I try to resist because the aim of this model is to show the fundamental functioning of the process of institutional change. I think that it is not well understood by many people. I am aware that I am leaving out a lot and also many things that are crucial if we want to effectively engage in economic change. But I think this fundament is still useful to start a discussion. The second disclaimer is that I’m building the model on a logic that draws from systems dynamics: you will see boxes and arrows that build a feedback loop. Now I have often expressed my scepticism about such ‘box-and-arrow’ models – I’m not a big fan of causal loop diagrams and how they are often used to map whole systems. I do see a use of such models, however, when we want to show some fundamental processes and patterns that have shown to be reasonably stable – they are widely accepted and are not part of a dynamically changing arrangement of causes and effects. Either because they are on a level of abstraction that allows for this stability (as in the case of the model I am going to present) or they are so engrained that they are very robust and unlikely to easily change (this is what systems dynamics people often call system archetypes). So, done with the disclaimers, on to the juicy bits now.

Projecting institutional change on the systems iceberg

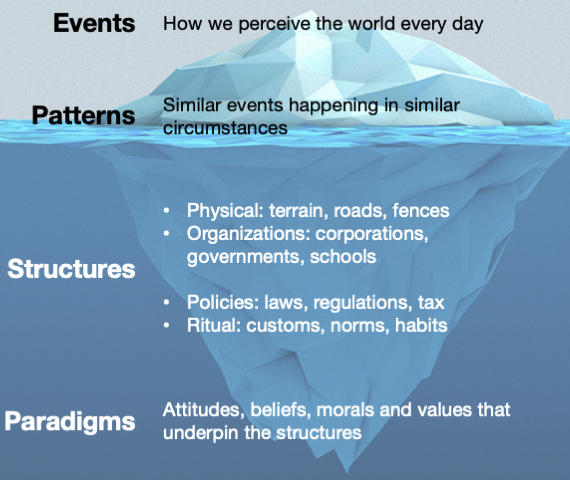

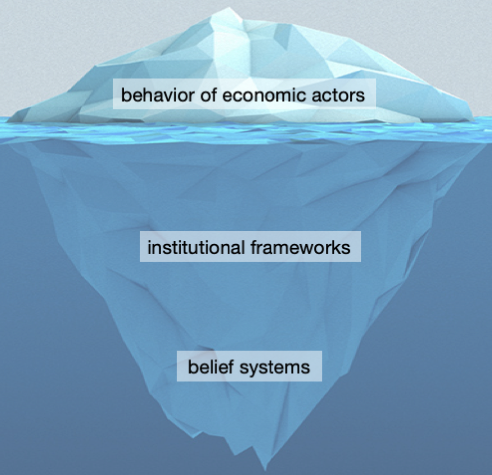

As mentioned, I’m using the systems iceberg as a canvas. Figure 1 shows the iceberg as it is generally used when talking about complex human systems. It differentiates between day-to-day events on the surface, then, just below the surface, persistent patterns of behaviour that string together events that seem to repeat in similar circumstances over time. Thirdly, the model talks about systems structures, which are under the surface and not easily visible. Some people further differentiate the structures into physical infrastructure (terrain, roads, etc.), organisations (organisation as a form of doing things in a group itself being a form of institution), policies (laws, regulations, tax codex, etc.) and rituals (customs, norms, habits, etc.) – even though some of these structures are clearly visible and not ‘under the surface’, but anyway. Then, further down and harder to spot, there is the level of the mental models contains attitudes, beliefs, morals and values that underpin the structures. I have now replaced the terms Patterns, Structures and Paradigms with the respective terms used in New Institutional Economics: behaviour of economic actors, institutional frameworks, and belief systems (see Figure 2).

The dynamics of institutional change

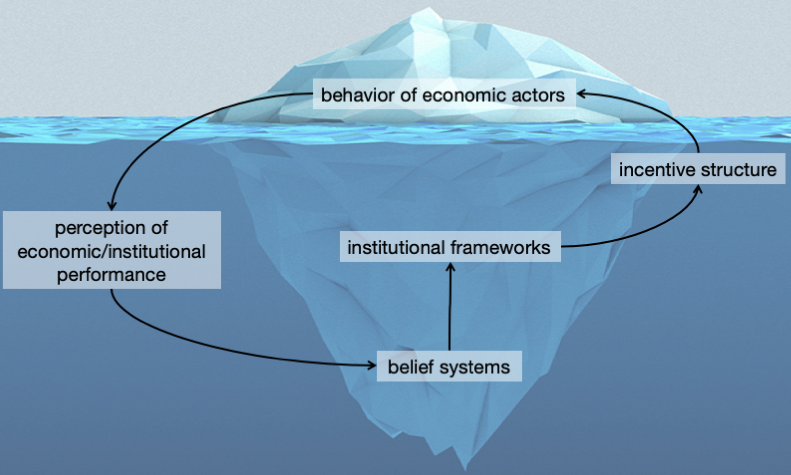

According to North, institutional change occurs when those people who are able to influence policy decisions perceive the current institutional framework as not performing effectively with regard to whatever measure of success they deem appropriate. North insists that institutional change is an intentional process shaped by actors who can achieve a certain amount of dominance through a combination of influence and power – it actually often happens by new actors getting in a position of influence and power rather than by existing power structures ‘changing their minds’. As a consequence, institutions continuously evolve based on how actors who can gain influence make sense of their perceived reality, how they evaluate institutional performance and the subsequent intention of these actors to adapt the institutions to optimise economic outcomes.

There is a feedback loop between dominant belief systems and the institutional landscape. Beliefs determine the structure and evolutionary direction of the institutional landscape. The institutional landscape in turn shapes the behaviour of the economic actors and ultimately determines economic performance. The perceptions of the actors on the effectiveness of the current institutional framework shape their beliefs, and in turn again determine the drive of the actors in the system to change and adapt the institutional landscape. The feedback loop is depicted in Figure 3.

Factors mitigating institutional change

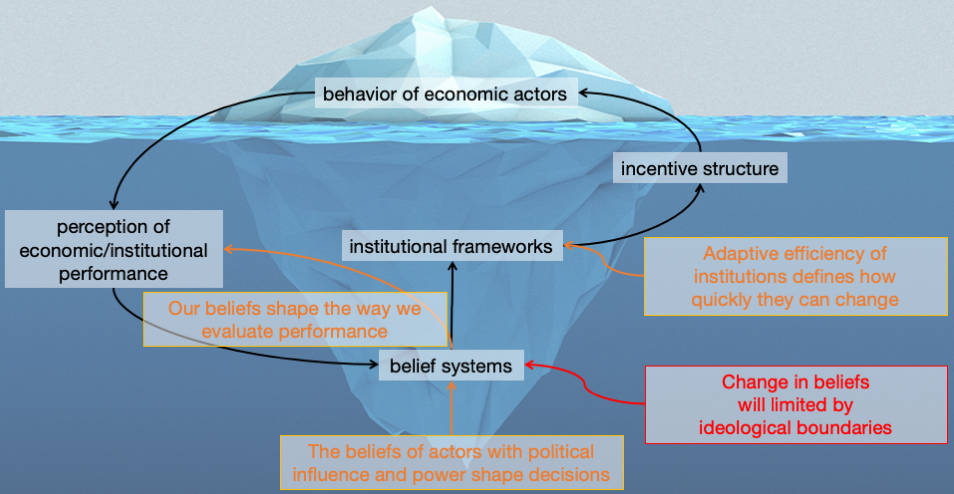

North talks about a number of factors that influence the feedback loop. First, the way we perceive and evaluate reality is shaped by our belief system, which is built by earlier experience and also a product of the cultural and social environment we have grown up in. We struggle to see things that are too far away from what we believe, or in other words what we have experienced before or what is part of the common experiences represented in our culture. This somehow forms a balancing loop that slows down institutional change and makes it inherently incremental. North in his book quotes Friedrich Hayek, who wrote in his book The Sensory Order: “The apparatus by means of which we learn about the external world is itself the product of a kind of experience. … The ‘model’ of the physical world which is thus formed will give only a very distorted reproduction of the relationships existing in that world; and the classification of these events by our senses will often prove to be false, that is, give rise to expectations that will not be borne out by events” (Hayek 1952, quoted in [1:33]). So just because the economic performance is not optimal, the relevant people might not perceive it as such as their belief systems blind them towards it. This happens for example when political elites in power do not perceive the hardship of the poor because they do not understand their reality.

A second related aspect that compounds this balancing feedback is that belief systems are constrained by ideological boundaries. If you identify with a certain ideology, e.g. socialism or neo-liberalism, it is much harder to value perceptions that question this ideology or adaptations of beliefs generally only happen within the boundaries of what the ideology allows for. This also links back to the point made above about the importance culture and the society in which we live. Here for example politicians might see the hardship of the poor but they still believe that a free market will rectify this eventually on its own.

If and how quickly institutions change also depends on the adaptive efficiency of the institutional framework. While some institutions like regulations might change relatively faster than for example social norms, also the overall speed of change might be different in different societies. Some societies are more open to change, particularly when the facts show that change is needed, while others might be generally more conservative and opposed to change. But it is then also the internal structure of institutions and how they interact with each other that influences the speed of adaptation and change.

Finally, there is the question of whose perceptions and beliefs count. North is quite adamant in that institutional change is predominantly driven by people with influence and power because they make decisions about policies, rules, regulations and other institutions that shape the incentive system for businesses. Hence, the more democratic and pluralistic a society is, the larger the group of people who can participate in this decision-making process. But in many cases, there are just a few people in power, strongly opposing any kind of economic change because the current situation predominantly benefits themselves at the expense of the large majority of people in the country. These larger dynamics that mitigate institutional change have been coined by Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson in their book ‘Why Nations Fail’ [2] as the vicious and the virtuous circles.

Why nations fail – it’s the institutions, stupid!

In their book Acemoglu and Robinson theorise that the reason for global inequality is that one of two sets of institutions dominates in a country and to a large extend determine whether it is rich or poor: either inclusive institutions or extractive institutions. In very general terms, inclusive institutions are pluralistic, participatory and create conducive conditions for economic actors to engage in business and for markets to work, such as secure private property, an unbiased system of law, and a provision of public services that provides a level playing field in which people can exchange and contract; they also must permit the entry of new businesses and allow people to choose their careers. Extractive institutions on the other hand concentrate power in the hands of one or a few people and the way the economy is structured is to create as much value as possible for these elites to extract and enrich themselves with.

With regards to institutional change, Acemoglu and Robinson identify two overarching dynamics, a vicious and a virtuous circle, confirming North’s argument that institutional change depends on who is influential. In the virtuous circle, inclusive institutions perpetuate inclusive institutions because they are based on pluralistic decision-making and this makes them fairly resilient to attacks from groups that want to establish more extractive institutions. As one mechanism of this virtuous circle, the authors mention the rule of law: “The rule of law is not imaginable under absolutist political institutions. It is a creation of pluralist political institutions and of the broad coalitions that support such pluralism.” [2:306]

The vicious circle, on the other hand, is somehow the opposite of the virtuous circle as it keeps extractive institutions in place, also giving them tremendous resilience. People in power benefit from the existing extractive economic institutions and have no reason to make them more inclusive. Extractive institutions also lead to infighting. But, as the so called ‘iron law of oligarchy’ states: “new leaders overthrowing old ones with promises of radical change bring nothing but more of the same.” [2:361]

So while institutions can change following the model outlined in this post, change is not easy as there are powerful balancing feedback loops in place that keep the institutional landscape largely as it is. This does not mean that change is impossible. There are a number of examples where there has been a change from extractive to inclusive institutions, including Great Britain, France and large parts of Western Europe in the 16th, 17th and 18th century and more recently in the 20th century the southern States of the USA and China – even though the latter is only related to more inclusive economic institutions without the necessary opening of the political institutions to be more inclusive. Acemoglu and Robinson contend: “Despite the vicious circle, extractive institutions can be replaced by inclusive ones. But it is neither automatic nor easy. A confluence of factors, in particular a critical juncture coupled with a broad coalition of those pushing for reform or other propitious existing institutions, it often necessary for a nation to make strides toward more inclusive institutions. Some luck is key, because history always and folds in the contingent way.” [2:426-427]

This has very important consequences for development work, but that’s definitely for another post.

References

[1] NORTH, D.C. 2005. Understanding the Process of Economic Change. Princeton University Press: Princeton, N.J.

[2] ACEMOGLU, D. & ROBINSON, J.A. 2013. Why nations fail : the origins of power, prosperity and poverty. Profile: London.

Title photo by Ross Findon on Unsplash

Thanks Marcus. I’m a fellow Next Stage Radical. This article is helpful. I’m pondering a transformation ar a large traditional organisation and pondering how to accelerate the pace of change given the speed of learning. Current thinking is that real change only happens during genuine crisis.

Thanks for the comment Alex. Change is inherently slow outside of crises. It would be great to explore in more detail how you are approaching your change organisation.