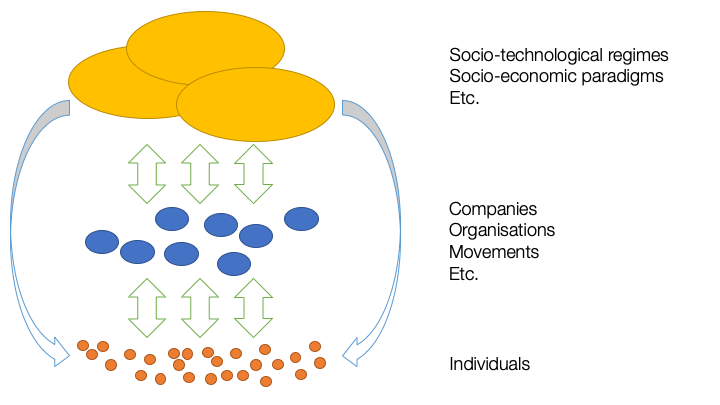

Can we as individuals change anything about climate change, given that we are so strongly entangled in a social-economic system that it sometimes feels we don’t have any free will whatsoever? I ask myself this question very often. Can organisations change things? I recently listened to a radio programme where environmental activists demanded that car manufacturers stop building large SUV cars. But why should they if the market (read: individuals) is still demanding these cars and it is legal for the manufacturers to produce them? How is change happening on the level of whole societies? Where are sustainability transitions happening? On the level of the individual, organisations or society? When reading up on sustainability transitions, there are discussions going on on all these different levels. There is the ‘macro’ level discussion that talks about transition dynamics on a societal level – this includes for example the move to non-fossil production of electricity or electric cars. Then, there is the level of discussion about changes on community and organisational level or on the level of social movements – where groups of people come together to change things or demand things, like the Fridays for the Future movement. Thirdly, there is the level of the individual with discussions on how to live a meaningful life in an era of transition or how to become a ’systems leader’. When I read through these different bodies of literature, I feel that the discussions on these different levels are often disconnected and sometimes seem unaware of each other. Sometimes they even seem inconsistent in their arguments or suggested strategies, even though they supposedly follow the same purpose to foster a transition towards a more sustainable society. What can we do to better link the different levels and to become more coherent in our strategy to change systems?

The societal-level transition literature includes concepts like innovation systems, social change, socio-technological transitions, socio-economic paradigms, deep transitions, socio-ecological resilience, etc. As an example, my business partner Shawn Cunningham describes technological change cycles in a blog post here. These concepts represent our understanding of the big picture of how societies, the technologies they use and their relation to the biosphere changes over time. What we get out of that understanding are often policy recommendations or rather generic high-level recommendations on what changes society should focus on and which principles might help to put this into practice. There is also an understanding that the systems we look at at this level are evolutionary and emergent, they cannot be designed but are rather a constant flow of stability and change.

Discussion on change at organisational, group or movement level include learning organisations, reinvented organisations, organisation unbound, social innovation, coalition-building, etc. They focus on relationships between people that either work together or otherwise share a common purpose and aim to achieve change. Here the big lessons are that effective organisations need to understand complexity, become better at learning and exploring, and some also think they need to loose much of the hierarchy that has dominated particularly large organisations for a long time. The idea of organisations is moving from a command-and-control type to a more self-organised and decentralised design. The difference to the societal level is that we can actually design large parts of organisations – or at least we can design the structure and constraints in which people will then act, like a scaffolding or architecture.

On the individual level, discussions include the need for more mindfulness, awareness-based action, expanded consciousness, etc. The mindfulness idea has spread quite widely over the last decade or more. The archetype of a good leader has shifted from a strong and dominant strategist (usually a man) who tells everybody what to do to a more understanding, mindful, fostering and coaching type (more feminine maybe – Harold Jarche recently wrote that our future is networked and feminine). Leaders for the age of systems look for distributed ways of decision making, and building on intrinsic motivation rather than extrinsic reward and punishment by giving their team members autonomy, mastery and purpose (three ways to build intrinsic motivation identified by Daniel Pink, see here).

I also wand to illustrate some of the inconsistencies (at least as I perceive them) between the literature about the three levels. Recently, the World Economic Forum (WEF) introduced its ‘CLEAR’ framework for leading systems change (see here), in which it synthesises a number of key elements that need to be present in systems change initiatives on the level of organisations and groups/movements. The elements are very similar across the literature. They generally start with actors coming together (convene and commit in the language of the WEF report), then map the current situation and figure out what’s wrong (look and learn), establish a common purpose or strategic intent (engage and energise), develop and implement interventions and monitor their effects (act with accountability), and then, based on the monitoring data, revise and adjust (review and revise). These steps are often derived from or are in some organisations enhanced by ideas and processes from design thinking. Hence, this literature often talks about designing solutions for a better future by bringing people together in groups with a common purpose.

In contrast, the literature on societal transformation level talks about an emergent future that cannot be designed. Agency is largely distributed, there is no single ‘systems leader’ that is able to steer us into and through a system transition. The dynamics are evolutionary, building on the need to create variety (often through the management of niches where new ideas are protected so they can be extensively tried), understanding and potentially influencing the selection dynamics, and retaining and amplifying designs that are fit for purpose. The literature also talks about the power of the incumbents to either co-opt or outright stop new and better designs. This literature does not talk about individual leaders bringing people together and helping them to design the right solutions. On the contrary, it talks about the need to create variety and diversity through many people experimenting on their own ideas with a necessary degree of independence to find different options. This is often called ‘fostering a process of self-discovery’. Once new designs are mature enough, and there is the right window of opportunity, fit for purpose designs can be scaled and potentially change the predominant way things are done (sometimes the scholars call this a ‘regime’ or an ‘architecture’). They are either integrated in the current regime or replace it altogether. They can also spill over and disrupt other sectors and industries different from the one they originate in (think computer manufacturers disrupting the music business), or be swallowed and even suppressed by incumbents and conservative policies.

The societal transition literature does not talk about designing a solution together to make things better but about creating diversity by having people try things, ideally isolated from each other as this would lead to more varied things being tried (having everybody in a group/room generally leads to more alignment). Initially, this seems to be a contradiction, but maybe it does not have to be. In Mesopartner we also developed a ‘process of exploration’ that pretty much mirrors the ideas of the WEF CLEAR framework. At the same time I have read enough on transition dynamics that I believe solutions cannot be designed but emerge based on an evolutionary dynamic. No, that is wrong. Solutions can be designed, but we don’t know in advance what the right design is. So we need to encourage people to create a great variety of different options. That means that from the perspective of an entrepreneur or start-up it is still about designing a solution they believe in, but from the societal or policy (or, indeed, systems change) perspective, its about creating variety, understanding and shaping selection mechanisms, and amplify designs that are fit for purpose. This is the evolutionary process that drives economic and social change.

For me the question how these different perspectives can be better integrated and how far the evolutionary process can be influenced in its direction becomes more and more pertinent. How can we for example influence the selection mechanisms so more sustainable solutions are selected, protecting us from the various environmental catastrophes we are heading towards? I also often get asked what organisations or other groups of people can do to contribute to the sustainability transition. The natural answer is to keep going and try to find solutions that they think can work – maybe explore the potential of different ways of doing things, so they already create some diversity within what they try. If many organisations do more of this exploration, the chances are that we find better designs for a sustainable future.

Some attempts are done to link the levels by scholars and practitioners. One example that comes to mind is the discussion about scaling social innovations (I wrote about this here). Interesting work is also done around dialogue, often going back to David Bohm’s work on dialogue, where he makes a clear connection between dialogue in a group and the work an individual needs to do in order to meaningfully participate in an effective dialogue (for example becoming more aware how his/her thoughts work and being mindful about that). Otto Scharmer has taken many different strands of work together in his ’Theory U’, where he explicitly links individual awareness and group action to create a better world ‘from the emergent future’. While this links the individual and the group, it does not make the link to the theories of societal transitions but also ends by assuming the bringing together a group of committed people you can essentially change the world.

There is definitely more to explore here.

Title image by Adri Tormo on Unsplash