Last week I was in Myanmar working with a market

systems development programme. The main task of this trip is to work on the project’s monitoring framework. To set the stage for that, we are working on revising the project’s theory of change (ToC).

A messy theory of change

Theory of Change is a bit of a contentious beast in my set of tools. As I am thinking and writing a lot on complexity and complex systems, I am aware that causality in complex systems can hardly ever be reduced to a straight line between two boxes and it is even more difficult to predict in advance how change will look like. It is not just that causalities are difficult to disentangle or predict in advance (it’s easier using hindsight), but that because of emergence there are other causalities at work than the linear material – billard-ball like – causality we are used to. But this is the topic of another blog post. So for me, Theory of Change is not an instrument to predict what change will happen but to create a coherent picture that explains why the project is doing what it is doing. Whether it contains any results or effects and lines from interventions to ultimate outcomes or whether it does only show how a set of unrelated safe-to-fail experiments interacts to create change is of less importance to me. Whether I use ToC at all really depends on the team. If I can get the team to grasp concepts of complex systems, attractors, dispositionalities, etc., I will not use a ToC approach but rather stay on the ‘purer’ complexity side of things. When a team is still strongly rooted in traditional development thinking where it is important to clearly define ideal future states, I will take the team from there and try to gently lead them towards recognising uncertainties and give them tools to deal with them, for example a complexity sensitive ToC.

No clear causal chain but a ‘space of the possible’

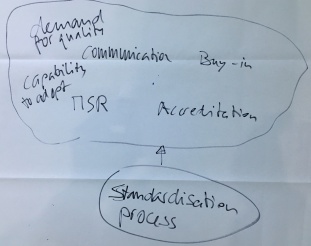

I have written about ideas to make ToC ‘complexity sensitive’ by using Cynefin. Here in Myanmar I have not used Cynefin explicitly. I used a simple heuristic to find the complex issues the project is grappling with: problems where there are multiple competing hypothesis about why they exist (and where data/evidence supports multiple competing hypothesis), and opinions on how to solve them diverge, can be categorised as complex. For these problems, instead of drawing clear lines between boxes, I encouraged the project team to create a ‘space of plausible changes’ that they believe could be the result of project interventions. While this does not allow to measure change along a neat causal path, it still creates a sort of anticipatory awareness towards possible signs for change the team can pick up in the field.

This time I also experimented with a new structure for the ToC. Rather than going along the familiar route of ‘intervention-output-outcome-impact’, I changed the ‘layers’ (not sure if this is the right word) of the ToC as follows:

- Intervention: This level broadly describes the interventions without going into detailed activities as they might change frequently. Intervention are seen as triggers for stakeholders to react to.

- Uptake: This is about the immediate change the project wants to trigger on the level of the partner the team engages with. Essentially, this is the justification of why we work with these partners. What is the change in behaviour that we want to see on that level?

- Interaction of interventions/with context: This is where the changes taken up by project partners start to interact with each other and are exposed to the context. For example, how would increased knowledge of farmers on cultivation and production technique play out in the reality of a very difficult market that drives down rather than demands quality.

- Systemic change: this is the layer where we look at wider patterns of persistent failure or underperformance and how they could be more beneficial.

Really interesting here is ‘layer’ three. Firstly, this is the place where individual interventions start to interact and where synergies between interventions come into play. But more importantly, here we explicitly take in to account the context and how the interventions interact with the context. This requires us to have a pretty good idea about the context, predominant attitudes, perceptions, belief systems, etc. Questions we asked were: What are farmers going to do with new knowledge? Are they reacting in a conservative way and say they will continue to do things the way they have always done? Or will they embrace it? And if they embrace it, what will be the reaction of the market on the improved product quality and/or quantity? This is where other interventions come into play, for example the work with the traders or other larger down-stream buyers of the product.

This is also the layer where different hypotheses on how something is going to play out can be taken into account. As written above, this is not about the ideal causal pathway we want things to play out. This is about discussing possible favourable patterns that can be stimulated and create anticipatory awareness of them so they can be picked up by monitoring. Also, this is about discussing unfavourable patterns in order to be able to recognise these early and dampen if necessary. A discussion about this uncertainty will hopefully also help the team to pick up totally unanticipated effects or changes.

During the work I realised that I need to rethink layer 4 as well. Systemic changes were actually ‘pulled down’ during the discussion into layer 3 as they are (hopefully) an result of interacting interventions and interactions with context. So layer 4 is developing more into depicting what we assume will happen in the market once these changes take place and in particular what will happen to the programme beneficiaries.

More work is needed and the team in Myanmar will be important to see how the structure needs to be adapted to be useful for them.