Recently I started a series on the development of a typology of systems change (the two previous articles are here and here). In this post, I want to introduce the concepts of ‘scaling out’, ‘scaling up’ and ‘scaling deep’ developed by scholars of social innovation. I want to link these concepts to my earlier thinking around the systems change typology and update it based on the new insights from this literature. At the end I will also voice a little critique on innovation-focused approaches to systems change.

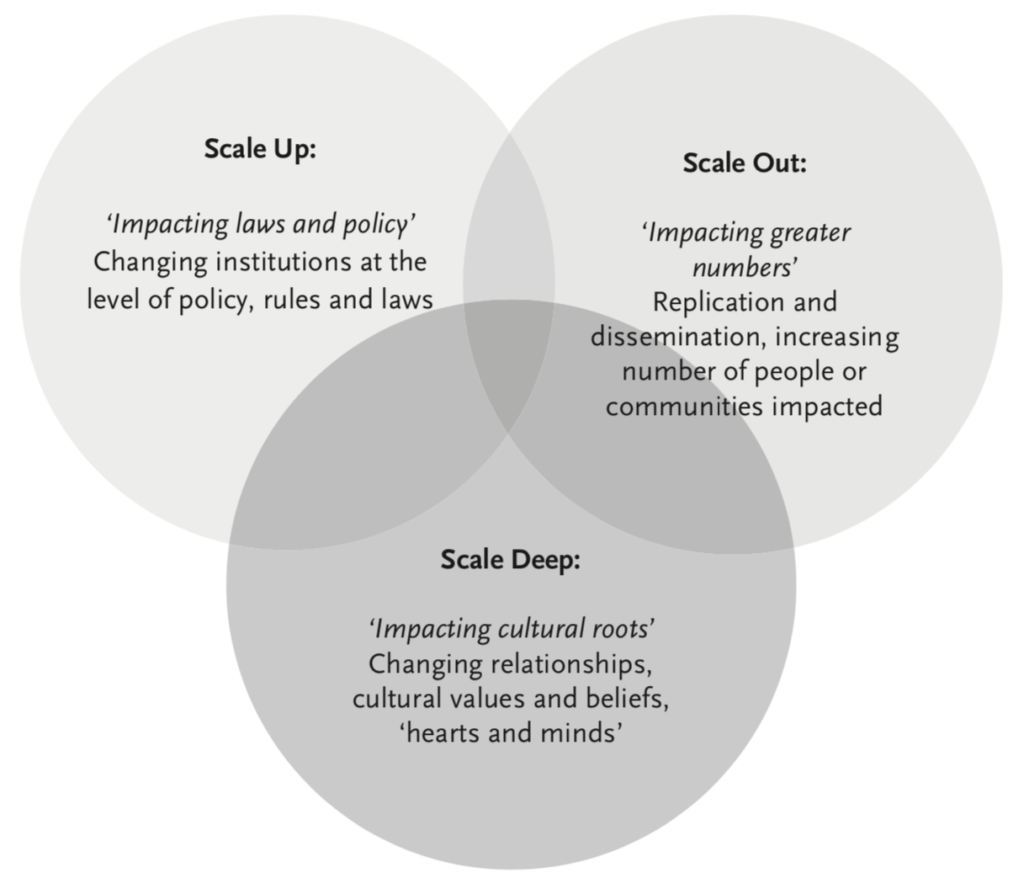

‘Scaling out’ refers to the most common way of attempting to getting to scale with an innovation: reaching greater numbers by replication and dissemination. ‘Scaling up’ refers to the attempt to change institutions at the level of policy, rules and laws. Finally, ‘scaling deep’ refers to changing relationships, cultural values and beliefs.

The differentiation between scaling out, scaling up and scaling deep was introduced by Michele-Lee Moore, Darcy Riddell and Dana Vocisano in a 2015 article in The Journal of Corporate Citizenship [1]. Moore and colleagues both draw from the literature – particularly the scholarly fields of strategic niche management (SNM) and social innovation – and from an empirical study they conducted with a number of grantees from the J.W. McConnell Family Foundation in Canada. SNM is a sub-field of the literature around socio-technical transition research I also refer to in my first article of the series.

In the outset of their article, Moore and colleagues ask [1:69]:

How can brilliant, but isolated experiments aimed at solving the world’s most pressing and complex social and ecological problems become more widely adopted and achieve transformative impact?

They then make the important point that … [1:69]

… [l]eaders of large systems change and social innovation initiatives often struggle to increase their impact on systems, and funders of such change in the non-profit sector are increasingly concerned with the scale and positive impact of their investments.

Hence, the starting point of the research is very similar to the one described by the Adapt-Adopt-Expand-Respond (AAER) framework (which I introduced in my first post in the series): a (social) innovation that is successfully addressing a particular problem or situation in one or a few specific contexts or niches.

Scaling out, up and deep

While AAER essentially describes one way of scaling from this starting point (‘scaling out’), Moore and colleagues add two further ways of scaling: ‘scaling up’ and ‘scaling deep’. For AAER, systemic change is achieved when the given innovation is adopted by players beyond the influence of the original innovator (what is called the ‘expand’ phase in the framework). This is usually tied to verifiable numbers, i.e. how many people can profit from an innovation that is expanded (i.e. copied) beyond the original innovator. Analogue, Moore et al. describe scaling out as ‘impacting greater numbers’.

‘Scaling out’ represents one of the types of systemic change I described in my initial typology: An innovation is introduced to rectify a problem in the current regime and, as it is in a symbiotic relationship with this regime, it is quickly scaled through replication and integrated as a new routine in the current regime. This type of innovations generally stabilise the regime – which is ok if one is in favour of this current regime. In this case, one would not talk about a system transition, but still about systemic change – as the innovation has reached scale and benefits many people.

The second type of systemic change I described does change the dominant regime, i.e. it would lead to transformative change on a system level. This happens if the innovations on the nice-level are competing with the current regime and they are mature and aligned/organised enough to take advantage of a disturbance of the regime coming from the landscape level. In this case, the regime would be replaced by a new one, characterised by the new innovations.

What Moore and colleagues’ work adds to this differentiation is that it describes two separate pathways to achieve transformative systemic change (or what they call Large System Transformation): by changing the institutions at the level of policy, rules and laws (‘scaling up’) and by changing relationships, cultural values and beliefs (‘scaling deep’).

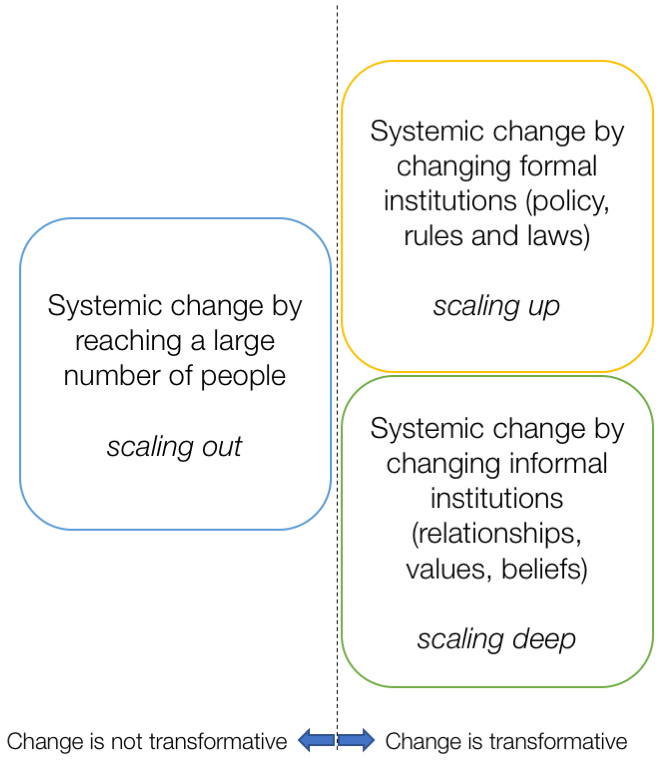

I appreciate the need to separate between scaling up and scaling deep. The way I interpret it, scaling up mainly targets formal institutions (Moore et al. mention policy, rules, and laws), while scaling deep mainly targets informal institutions (relationships, cultural values, and beliefs). It is clear that you would need totally different approaches to tackle these two. Hence, I would like to adopt this separation into my systemic change typology. It now has three domains, as illustrated below.

A point of contention: use of evolution instead of intentional design

Moore and colleagues’ model adds a lot of depth to the discussion about scaling, taking the focus away from sheer numbers to be reached and pointing to the importance of seeking change on the level of the current institutional and cultural regime. My contempt with the framework is that it still starts from a niche-level innovation that is intentionally designed to overcome a particular problem and then asks how this solution can be scaled. Hence, it in a way still takes a problem solving mentality, rather than a mentality that is based on emergence and evolution. The solution still depends on experts and their assumptions and biases.

What do I mean by that? The basic argument that I want to make here is that if we want to see a system exhibit specific qualities (e.g. inclusiveness, gender equity, sustainability, etc.), it is more effective to change the selection environment that innovations in a system are exposed to so solutions that are exhibiting these qualities are more likely to be adopted rather than to design individual solutions to all kinds of problems that exhibit these qualities.

I’m basing this argument on the realisation by many scholars that institutional and socio-technical development essentially happens in an evolutionary way [2]. Evolution is based on three mechanisms: the creation of variation, selection, and amplification. In nature, the creation of variety happens through random mutations, while in social systems, it happens through people trying different solution combinations to their pressing problems (i.e. innovating). This process happens in the three domains of physical technologies, social technologies, and business plans (see [3] for a brief description of these domains).

Eric Beinhocker describes evolution as [4:187] …

… a general-purpose and highly powerful recipe for finding innovative solutions to complex problems. It is a learning algorithm that adapts to changing environments and accumulates knowledge over time.

With “general-purpose”, Beinhocker means that evolution is not unique to biology and can only be used in a metaphorical way when talking about social and technological change, but that it is indeed happening in various domains, including the latter.

Beinhocker further contends [4:213]:

Mathematics and evolutionary theorists have explored a variety of alternative search algorithms on different [fitness] landscape shapes. Some are better for searching perfectly random landscapes, and some are better for searching highly ordered and regular landscapes. But for landscapes that are in between, are rough-correlated, and have complex features such as plateaus, holes, and portals, evolution is hard to beat. And when the landscape is constantly changing, when the search problem is a dynamic one, when one must balance the tension between exploring and exploiting – evolution truly is the grand champion.

In other words, if we want to see large scale systems change in a particular direction, we should not ask ourselves how we solve all problems by using inclusive innovations. Rather, we should take a step up and influence the institutional environment so the way the selection pressure shapes the innovations that are selected and amplified makes the system more inclusive. I feel this is really hard to explain. This does not mean that everybody should stop innovating. If we are at the coal face of innovation, we need to go on. Indeed, the institutional framework conditions should encourage a vivid process of self-discovery happening all over the system. If there is no variety, there is no selection. The more things that are tried, the more likely it is that we find strong solutions.

I guess in the end this is not too different from the argument that Moore and colleagues make. We need to go beyond scaling out innovations by copying and pasting. We need to change the institutional level. What I’m trying to say is that the change we bring to the institutional level does not have to start from an innovation asking how it could be scaled. Rather, it can start from the level of principles or qualities we as a society see that we need more of in our systems and an adjustment of the selective pressure while at the same time allowing for innovation to be broad and innovators to be courageous.

There is so much to add here. The whole study of institutional change is extremely important here. How can the institutions that shape innovation themselves become flexible and adaptive? How can the better anticipate future directions of change and prepare communities and companies?

Reference

[1] MOORE, M.-L., RIDDELL, D. & VOCISANO, D. 2015. Scaling Out, Scaling Up, Scaling Deep: Strategies of Non-profits in Advancing Systemic Social Innovation. Journal of Corporate Citizenship, Vol. 2015(58):67-84.

[2] NELSON, R.R. & WINTER, S.G. 1982. An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA.

[3] CUNNINGHAM, S. & JENAL, M. 2016. Rethinking systemic change: economic evolution and institutions. Discussion Paper. The BEAM Exchange. https://beamexchange.org/resources/860/

[4] BEINHOCKER, E.D. 2006. The Origin of Wealth: Evolution, Complexity, and the Radical Remaking of Economics. Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA.

Always enjoy your blogs.

Have you played with Wilbur’s 4 quadrants?

Scaling Up = External Collective change.

Scaling Deep = Internal Collective change.

Scaling Out = External Individual change (kind of).

Scaling In = Internal Individual change?

I also wonder whether you are pointing to a more co-evolutionary approach to systems change, so that the three approaches can be happening more simultaneously rather than one leading to another?

I also wonder what scaling out really means, and whether context matters enough for scaling out to mean re-growing solutions based on principles, and not simply replicating bigger and better, and I guess that is where the scaling up starts to meet the scaling out, etc. Patton’s work on Principles-Based evaluation might have a part here as well.

Pondering…

Hi Bhav. Always enjoying your comments … 😉

I am vaguely familiar with Wilbur’s work but it’s not part of my circle of competence. So I could not say if your attempt to match the scaling logic to his quadrants is useful, even though it sounds sensible.

Definitely co-evolutionary. All three levels need to evolve together, otherwise we won’t advance. That is why I am saying that people should not stop innovating, but what I’m saying is that policy advice should more strongly look at the selection pressure. Also foundations could think how they could work more on that level rather than – or even better in addition to – supporting individual innovators.

The principles-based scaling out is actually one mechanism that Moore and colleagues found in their study and present in their paper. It is indeed allowing for more variation on a theme.

Hi, I’m one of the authors and I did intend Scaling Deep to refer to Wilber’s Upper Left and Lower Left quadrants, Bhav. Nice correlating.

I also really agree with the critique around innovation-based approaches mostly not addressing wider contexts. This work comes out of the Resilience-informed social innovation work of Dr. Frances Westley and the Waterloo Institute for Social Innovation and Resilience, which centres a definition of social innovation that builds on Giddens and is defined by changes in basic routines, resource flows, rules, laws and cultural values within a social system. This more systemic version does differ significantly from most definitions of social innovation.

I’ve written more about this and also large-scale systems change and the agency to advance it, and would be happy to share. I’ve also written about systemic social change and sustainability from an integral (Wilber) perspective in the book Integral Ecology.

Hi Darcy. Thanks for commenting on my blog post. And thanks for your great article. I have come across Frances Westley’s work and the institute and I’m am very keen to read more of it. I think social innovation has an important role to play in the transformation of society that is needed for us to face our current challenges.

Thanks a lot Marcus! Sven