This blog post is about what I see as one of the most important papers linking the complexity sciences to development and humanitarian efforts – at least it is for me personally, but I think it also takes a very important position in the discussion in general.

This blog post is about what I see as one of the most important papers linking the complexity sciences to development and humanitarian efforts – at least it is for me personally, but I think it also takes a very important position in the discussion in general.

The paper has the title ‘Exploring the science of complexity: Ideas and implications for development and humanitarian efforts’ and is authored by Ben Ramalingam (author of the blog Aid on the Edge of Chaos) and Harry Jones with Toussaint Reba and John Young. The paper can be downloaded here.

Why do I think is the paper so important? For me personally it was the first paper I read that explicitly linked the two domains (complexity science and international development) and it does that in a very comprehensive and systematic manner.

Ramalingam and colleagues go back to the origins of complexity sciences and put it into context by showing applications in the social, political and economic realms. They unpack the complexity sciences and present them in ten key concepts divided into three sets, i.e., complexity and systems, complexity and change, and complexity and agency. Here an overview taken from p 8. of their paper:

Complexity and systems: These first three concepts relate to the features of systems which can be described as complex:

- Systems characterised by interconnected and interdependent elements and dimensions are a key starting point for understanding complexity science.

- Feedback processes crucially shape how change happens within a complex system.

- Emergence describes how the behaviour of systems emerges – often unpredictably – from the interaction of the parts, such that the whole is different to the sum of the parts.

Complexity and change: The next four concepts relate to phenomena through which complexity manifests itself:

- Within complex systems, relationships between dimensions are frequently nonlinear, i.e., when change happens, it is frequently disproportionate and unpredictable.

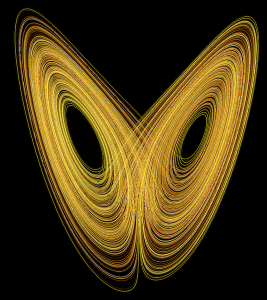

- Sensitivity to initial conditions highlights how small differences in the initial state of a system can lead to massive differences later; butterfly effects and bifurcations are two ways in which complex systems can change drastically over time.

- Phase space helps to build a picture of the dimensions of a system, and how they change over time. This enables understanding of how systems move and evolve over time.

- Chaos and edge of chaos describe the order underlying the seemingly random behaviours exhibited by certain complex systems.

Complexity and agency: The final three concepts relate to the notion of adaptive agents, and how their behaviours are manifested in complex systems:

- Adaptive agents react to the system and to each other, leading to a number of phenomena.

- Self-organisation characterises a particular form of emergent property that can occur in systems of adaptive agents.

- Co-evolution describes how, within a system of adaptive agents, co-evolution occurs, such that the overall system and the agents within it evolve together, or co-evolve, over time.

In great detail they explain every concept, give examples and discuss the implications of the concepts for the development system.

I like the paper because it really brings together all those important concepts in an accessible way. Although the paper is pretty long (89 pages all in all), it is not at all a boring read. In the conclusion part of the paper, the authors also describe the difficulty of presenting such an intricate matter as complexity sciences, itself being not a unified scientific discipline:

[…] it is useful to note that scientific knowledge is usually characterised with reference to the metaphor of a building. The ease with which the terms ‘foundations’, ‘pillars’ and ‘structures’ of knowledge are used indicates the prevalence of this architectural metaphor. Our difficulty was in trying to represent complexity science concepts as though they were parts of a building. They are, in fact, more like a loose network of interconnected and interdependent ideas. A more detailed look highlights conceptual linkages and interconnections between the different ideas. The best way to see how they fit together in the development and humanitarian field would be to try to apply them to a specific challenge or problem. […] Based on our reading, however, a grand edifice may never be erected along the lines of, for example, neoclassical economics. If this is the case, it may be that we need to become better accustomed to a network-oriented model of how knowledge and ideas relate to each other.

For me, it is intriguing how the science of complexity not only defies scientific practices by diverting from the pure deductive and inductive approaches and combining them but also evaded characterizations in ‘traditional’ scientific schemes such as the building mentioned above. This reminds me of the book ‘Complexity and Postmodernism’ by Paul Cilliers, which I started reading but I got stuck somewhere in the middle, overwhelmed by his theory and language. I hope that I will finish it some day and report on that here.

The authors also try to answer a number of questions around the topic of the application of complexity to development and what it means for example for international donors. A few quotes from the concluding remarks:

In our view, the value of complexity concepts are at a meta-level, in that they suggest new ways to think about problems and new questions that should be posed and answered, rather than specific concrete steps that should be taken as a result.

[…]

As well as use by implementing agencies, an understanding of complexity must also be built into the frameworks of the donors and others who hold the power to determine the shape of development interventions. This may be easier said than done – complexity requires a shift in attitudes that would not necessarily be welcome to many working in Northern agencies. For example, such a shift may require adjusting away from the ‘mechanistic’ approach to policy, or being prepared to admit that most organisations are learning about development interventions as they go along, or being transparent about the fact that taxpayers’ money may be spent on a project that does not guarantee results. It may mean having smaller, but better programmes.

[…]

At the start of our exploration, our view was simply that complexity would be a very interesting place to visit. At the end, we are of the opinion that many of us in the aid world live with complexity daily. There is a real need to start to recognise this explicitly, and try and understand and deal with this better. The science of complexity provides some valuable ideas. While it may be impossible to apply the complexity concepts comprehensively throughout the aid system, it is certainly possible and potentially very valuable to start to explore and apply them in relevant situations.

To do this, agencies first need to work to develop collective intellectual openness to ask a new, potentially valuable, but challenging set of questions of their mission and their work. Second, they

need to work to develop collective intellectual and methodological restraint to accept the limitations of a new and potentially valuable set of ideas, and not misuse or abuse them or let them become part of the ever-swinging pendulum of aid approaches. Third, they need to be humble and honest about the scope of what can be achieved through ‘outsider’ interventions, about the kinds of mistakes that are so often made, and about the reasons why such mistakes are repeated. Fourth, and perhaps most importantly, they need to develop the individual, institutional and political courage to face up to the implications.

I’d recommend anyone who works in international development and is interested in complexity to read this paper. It is a perfect entry point also for people with no background in complexity science.